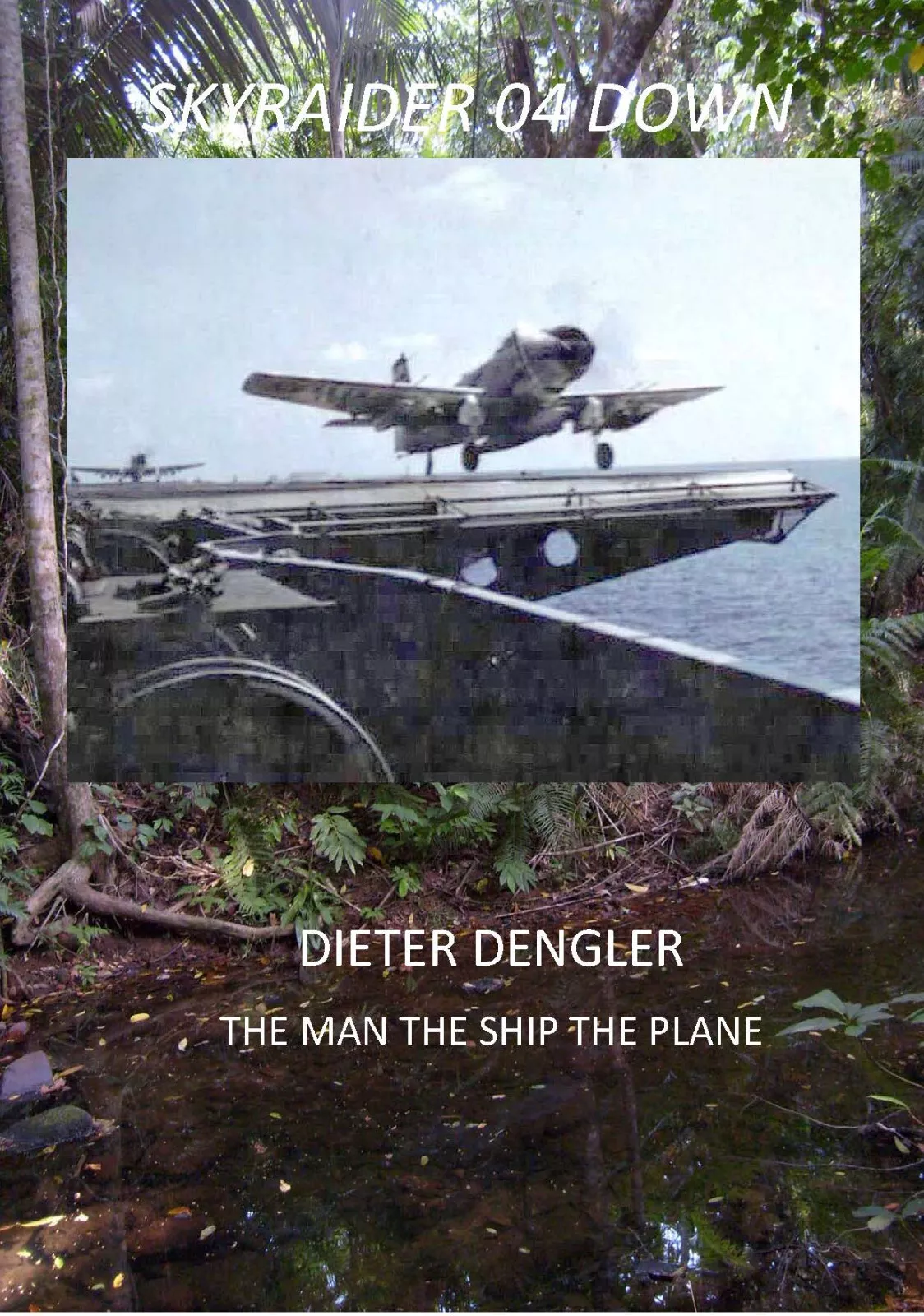

Original illustration (schematic): carrier deck motif representing Skyraider-era naval operations.

Executive Summary

Dieter Dengler (1938–2001) was a U.S. Navy attack pilot whose A‑1 Skyraider was shot down over Laos on 1 February 1966. Captured by Pathet Lao and held in brutal conditions alongside other prisoners, he engineered an escape on 29 June 1966 and survived alone in the jungle until a U.S. Air Force pilot sighted him and rescue forces extracted him in July. His story, told in his memoir Escape from Laos, Bruce Henderson's Hero Found, and Werner Herzog's documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly (and dramatized in Rescue Dawn), remains one of the most compelling accounts of human endurance and the Vietnam War's prisoner‑of‑war experience. Based on extensive research documented in Charles E. MacKay's authoritative biography Dieter Dengler, Skyraider 04 Down, the Man the Ship the Plane, this comprehensive analysis presents the complete story of Dengler's remarkable life, from wartime childhood in Germany through his service as a U.S. naval aviator, capture and escape in Laos, and enduring legacy.

Early Life in Germany (1938–1956)

Dengler was born on 22 May 1938 in Wildberg, Württemberg, in Germany's Black Forest. His formative years unfolded amid wartime scarcity and its aftermath. His father, drafted into the German Army early in the war, was killed on the Eastern Front during the severe winter of 1943–1944, leaving the family in deep poverty. Dengler later recalled scavenging for food and even boiling wallpaper paste for its wheat content during the leanest months. He apprenticed as a blacksmith in his teens—hard, often violent work that he credited for forging the toughness, discipline, and problem‑solving he would later lean on in captivity.

The book gives details of Dengler's early life in Germany, his moving to the United States, his education (he lived in a van) and his induction into the United States Navy. This comprehensive coverage ensures that Dengler's formative experiences are properly documented, providing context for understanding his later achievements and character development. The documentation of his early life demonstrates the comprehensive research methodology employed in documenting his complete biography.

A formative moral example came from his maternal grandfather, who refused to support the Nazi regime at the ballot box and suffered forced labor and public humiliation for it. Dengler repeatedly cited this example as one reason he refused to sign propaganda denunciations while a prisoner in Laos, even when doing so might have eased his treatment. Another seed was planted even earlier: a low‑flying Allied fighter over Wildberg impressed him so deeply as a child that he resolved to become a pilot. This early inspiration illustrates how formative experiences shaped Dengler's life trajectory and contributed to his eventual achievements.

Emigration and the American Dream (1956–1960)

At 18, Dengler left postwar Germany for the United States with little money and no guarantees. He reached New York after a difficult journey, spent nights without lodging, and took odd jobs while searching for a pathway into aviation. He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in 1957 and completed basic training at Lackland AFB. Although skilled and industrious—he worked as a mechanic and gunsmith—he found no path to the cockpit without a college degree. After his enlistment, he moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, studied aeronautics at San Francisco City College and the College of San Mateo, and continued the long, step‑by‑step climb toward pilot training.

Dengler's educational journey, including living in a van while pursuing his studies, demonstrates his determination and resourcefulness. This period of his life illustrates the challenges faced by immigrants seeking to achieve their dreams in America, and the persistence required to overcome obstacles. His success in eventually achieving his goal of becoming a pilot demonstrates how determination and hard work can overcome significant challenges.

Navy Aviation Cadet to Fleet Pilot (1960–1965)

Accepted into the U.S. Navy’s Aviation Cadet program, Dengler advanced through ground school and primary to advanced training—earning his wings in an era that demanded exacting standards and intense airmanship. He qualified on the Douglas A‑1 Skyraider, the last of the great piston attack aircraft, noted for its ruggedness, heavy weapons carriage, and extraordinary loiter time. By late 1965, he was assigned to Attack Squadron 145 (VA‑145), deploying aboard USS Ranger to the Western Pacific as U.S. operations escalated in Southeast Asia.

The A‑1’s distinctive strengths shaped Dengler’s routine: long cycles in the cockpit, often in demanding weather, coordinating with strike packages, tankers, forward air controllers, and search‑and‑rescue (SAR) assets. The Skyraider’s ability to fly low and slow for extended periods made it ideal for SAR escort—“Sandy” missions—as well as for close air support against time‑sensitive targets.

Navy Aviation Cadet to Fleet Pilot (1960–1965)

Accepted into the U.S. Navy's Aviation Cadet program, Dengler advanced through ground school and primary to advanced training—earning his wings in an era that demanded exacting standards and intense airmanship. He qualified on the Douglas A‑1 Skyraider, the last of the great piston attack aircraft, noted for its ruggedness, heavy weapons carriage, and extraordinary loiter time. By late 1965, he was assigned to Attack Squadron 145 (VA‑145), deploying aboard USS Ranger to the Western Pacific as U.S. operations escalated in Southeast Asia.

The book Dieter Dengler, Skyraider 04 Down, the Man the Ship the Plane provides comprehensive coverage of Dengler's life and times, including the history of the USS Ranger and her deployments off Vietnam. The book documents how Dengler flew the Douglas Skyraider and includes the aircraft history with Royal Navy service and service in Sweden, providing context for understanding the Skyraider's international significance and operational versatility.

The A‑1's distinctive strengths shaped Dengler's routine: long cycles in the cockpit, often in demanding weather, coordinating with strike packages, tankers, forward air controllers, and search‑and‑rescue (SAR) assets. The Skyraider's ability to fly low and slow for extended periods made it ideal for SAR escort—“Sandy” missions—as well as for close air support against time‑sensitive targets. This operational versatility made the Skyraider invaluable during the Vietnam War period, when flexible aircraft capable of operating in challenging conditions were essential.

VA‑145's operations from USS Ranger represented a crucial component of U.S. naval aviation capability during the Vietnam War. The carrier's deployments off Vietnam enabled sustained air operations against targets in Southeast Asia, with Skyraider squadrons providing essential close air support and SAR escort capabilities. Dengler's assignment to VA‑145 placed him at the forefront of these operations, flying missions that demonstrated the Skyraider's enduring value in combat conditions.

The Skyraider's service history extended beyond U.S. operations to include Royal Navy service and Swedish service, demonstrating the aircraft's international significance and operational versatility. The book includes details of the Scottish Aviation Skyraider for Sweden in the appendix, providing comprehensive coverage of the aircraft's international service history. This global deployment demonstrates the Skyraider's effectiveness and the international recognition of its capabilities.

USS Ranger Operations and Carrier Aviation

USS Ranger (CV-61) was a Forrestal-class aircraft carrier that played a crucial role in U.S. naval operations during the Vietnam War. The carrier's deployments off Vietnam enabled sustained air operations against targets throughout Southeast Asia, with air wings comprising multiple aircraft types operating in coordinated strike packages. The book provides comprehensive coverage of USS Ranger's history and deployments, documenting the carrier's operational role in supporting U.S. military operations in Southeast Asia.

Carrier operations during the Vietnam War required sophisticated coordination between aircraft types, with Skyraiders providing essential capabilities that complemented jet aircraft. The Skyraider's ability to loiter over targets for extended periods, operate at low altitudes, and deliver precision ordnance made it invaluable for missions requiring sustained presence and accurate firepower. These capabilities were particularly important for SAR operations, where aircraft needed to remain on station for extended periods while escorting rescue helicopters.

For comprehensive coverage of carrier aviation history and operations, see Naval Aviation History: From Seaplanes to Supercarriers, which provides detailed analysis of aircraft carrier development and operational procedures. The evolution of carrier operations from early seaplane operations to modern carrier aviation demonstrates the sophisticated systems and procedures that enabled effective naval air power projection.

The book documents how Dengler flew off the USS Ranger, CV-61, on his final flight. His squadron was Attack Squadron VA-145, and in his last operational sortie he flew the Douglas A-1 Skyraider. This detailed documentation provides precise information about Dengler's operational context and the aircraft he flew, ensuring accurate historical understanding of his service and the circumstances of his shoot-down.

Mission, Shoot‑down, and Capture (1–2 February 1966)

On 1 February 1966, during a mission over Laos, Dengler's A‑1 was struck by ground fire. He executed a forced landing in mountainous jungle terrain and attempted evasion. Local forces captured him the next day. Early interrogations and transit were brutal: he was bound, beaten, hung in painful positions, exposed to biting insects, and submerged to the point of near drowning. He refused to sign political statements and remained focused on survival—observing routines, guard habits, and the geography he could glean from the environment.

The book provides a thrilling account of his capture, imprisonment and escape based on CIA reports, ensuring that the narrative is grounded in authoritative intelligence documentation. These CIA reports provide crucial insights into the conditions Dengler faced and the circumstances of his capture, ensuring factual accuracy in documenting this crucial period of his experience. The use of intelligence reports demonstrates the comprehensive research methodology employed in documenting Dengler's story.

Dengler's shoot-down occurred during a period of escalating U.S. operations in Southeast Asia, with naval aviation playing a crucial role in supporting ground operations and conducting interdiction missions. The Skyraider's operational versatility made it suitable for a wide range of missions, from close air support to reconnaissance and SAR escort. Dengler's mission on 1 February 1966 was part of this broader operational context, demonstrating the intensity and scope of U.S. naval aviation operations during the Vietnam War period.

Camp Life: Disease, Starvation, Resolve

Dengler was eventually moved to a makeshift prison camp near the village of Par Kung, where he encountered other prisoners—Americans, Thais, and Chinese among them—including Air America crewman Eugene DeBruin and U.S. Navy aviator Duane W. Martin. Conditions were dire: legs and necks shackled to bamboo; emaciation from minimal rations; constant dysentery; skin infections and leeches; and the psychological wear of isolation. Even in these conditions, the prisoners traded knowledge—navigation tricks, snare setting, foraging cues—and quietly debated escape timelines.

When guards hinted that executions might be imminent, the calculus changed. Dengler and his fellow prisoners finalized an escape plan coordinated around guard routines, weather, and the simple fact that the jungle—while deadly—offered cover and food if one knew where to look. Dengler’s mechanical ingenuity (forging makeshift tools, studying locks, assessing weapon conditions) and his commitment to never sign propaganda gave the group a moral and practical center.

Escape into the Jungle (29 June 1966)

On 29 June 1966, the prisoners executed their plan, overpowering guards and seizing weapons. The group split. Dengler moved with Lt. Duane W. Martin toward the Mekong basin, navigating by river courses and sun lines under the forest canopy. Their rations were negligible. They relied on foraged plants, occasional small game, and rainwater pooled in leaves or collected in improvised containers. Leech removal, foot care, and water discipline became as critical as avoiding pursuers.

Dengler's was the first escape from Laos in 1966, making his achievement particularly significant in the context of POW operations during the Vietnam War. This historical distinction demonstrates the extraordinary nature of his escape and the challenges he overcame in achieving freedom. The book documents this achievement comprehensively, ensuring that Dengler's accomplishment receives proper recognition within the broader context of Vietnam War POW operations.

The escape was not only a test of endurance but of judgment under uncertainty—when to move versus hide, which ridge line to follow, whether a village represented help or mortal danger. In a tragic encounter, a villager killed Martin after an approach went wrong, forcing Dengler back into solo evasion. Malnourished, feverish, and with lacerated feet, he pressed on—driven by the will to survive and a disciplined focus on the fundamentals he could control: hydration, shelter, a signal plan if aircraft appeared, and incremental movement toward friendly lines.

Dengler's solo survival in the jungle represents one of the most remarkable achievements in survival literature. His ability to maintain discipline, make sound decisions under extreme stress, and persist despite overwhelming challenges demonstrates exceptional human resilience. The book's comprehensive documentation of this period ensures that Dengler's achievement is properly understood and recognized within the broader context of survival and escape literature.

Historical Significance and First Escape

Dengler's escape holds particular historical significance as the first successful escape from Laos in 1966. This achievement demonstrated the possibility of escape from Pathet Lao captivity and provided valuable intelligence about prison camp conditions and operational procedures. The escape's success validated the importance of preparation, observation, and disciplined execution in achieving escape objectives.

The book's companion relationship to Soaring With Wings: Percy Pilcher Wants To Fly creates an interesting connection between two remarkable aviation stories. While Pilcher's story represents early aviation pioneering, Dengler's story represents the operational application of aviation skills in challenging circumstances. Both stories demonstrate the human determination and skill that characterize aviation achievement across different eras and contexts.

Signal, Sighting, Rescue (July 1966)

After weeks alone, Dengler spotted a U.S. aircraft and improvised a high‑contrast signal using a parachute flare canopy and cleared brush. A U.S. Air Force pilot sighted him (the widely credited sighting was by Maj. Eugene P. Deatrick, flying an A‑1 in the area), relayed the contact, and triggered a rescue effort. Within days, U.S. search‑and‑rescue helicopters—escorted by fixed‑wing assets—pulled Dengler out. He reportedly weighed barely 98 pounds when recovered. The professionalism and persistence of Air Force SAR units and Navy/Marine coordination in contested airspace were decisive.

Hospitalization, Debrief, and Decorations

Medical teams stabilized Dengler and began careful refeeding to avoid refeeding syndrome. Intelligence debriefs reconstructed the camp layout, guard routines, routes of movement, and conditions other prisoners faced. The Navy recognized his valor, endurance, and leadership with high decorations—including the Navy Cross as the service’s second‑highest award for valor—along with the Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star with combat “V,” Purple Heart, Air Medal, and unit citations. His survival narrative was unusual not only for the escape itself but for the tactical insights it yielded about camps in Laos and the realities of jungle evasion.

Return to Flight: Airline and Test Pilot

Dengler remained in the Navy for roughly a year, receiving promotion and jet transition training, then separated and flew commercially, including with Trans World Airlines. He also worked as a civilian test and demonstration pilot, a path that entailed risk; he survived multiple crashes. A lifelong aviator, he restored and flew a classic Cessna 195 and appeared at air shows—continuing to educate audiences about airmanship, SAR, and survival.

Return to Laos (1977)

In 1977, Dengler returned to Laos and visited the area of his former imprisonment. Accounts describe a reception by local authorities and a journey that brought him back to the remains of the camp. For survivors of captivity, such returns often serve both historical and personal purposes—ground‑truthing the record and offering a measure of closure.

Personal Life, Health, and Final Years

The psychological aftermath of captivity followed Dengler, as it did many former POWs. He spoke candidly about lingering effects—startle responses, nightmares, and the way scarcity imprints itself on habit. In 2000, he was honored in the Gathering of Eagles program, sharing professional lessons with military aviators. In 2001, after an ALS diagnosis, he took his own life on 7 February. Dengler was buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. Friends, colleagues, and historians have emphasized not only his wartime endurance but his lifelong kindness, craftsmanship, and humility.

Books, Film, and Historical Record

Dengler’s own memoir, Escape from Laos, anchors the primary narrative. Bruce Henderson’s Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam War contextualizes the biography with interviews and archival work. Werner Herzog’s Little Dieter Needs to Fly (documentary, 1997) offers a deeply personal portrait, which he later dramatized in Rescue Dawn (2006). These works, alongside official citations and unit histories, form a coherent record when read together, helping separate dramatic embellishment from the sober, documented timeline.

Decorations and Official Citations

Dengler’s decorations reflect both combat performance and extraordinary conduct as a prisoner of war. Among them, the Navy Cross recognizes his conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity; the Distinguished Flying Cross and Air Medal attest to aviation skill and heroism; the Bronze Star Medal with combat “V” denotes valor under enemy action; and the Purple Heart acknowledges wounds sustained in service. Unit citations and theater campaign awards place his story within the wider coalition effort in Southeast Asia. Reading the verbatim award citations—where available—provides precise language around actions, dates, and circumstances.

Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Lessons

While modern SERE curricula evolved over decades, Dengler’s experience anticipates several enduring principles. First, prioritize water and foot care: dehydration and infected wounds are silent attriters. Second, observe before acting: pattern analysis of guards, weather, and terrain often creates openings unavailable to force. Third, discipline under coercion: clear personal lines (e.g., refusing propaganda statements) can stabilize group cohesion, even as prisoners balance compliance for survival with resistance for integrity. Fourth, signal preparation: any high‑contrast material (fabric, smoke, ground marks) should be pre‑positioned for fleeting aircraft passes. Finally, team knowledge‑sharing: small skills—knots, snare setting, edible plant identification—compound into survivability.

A‑1 “Sandy” SAR Doctrine: Why It Mattered

Combat search‑and‑rescue in Southeast Asia fused helicopters with fixed‑wing escorts. The A‑1’s torque, wing area, and ordnance carriage made it a superb helicopter shepherd: it could fly tight turns at low speeds, suppress ground fire with guns and rockets, and mark targets with smoke. “Sandy” pilots carried radios for coordination with downed airmen, FACs, and Jolly Green Giants. Dengler’s recovery sits in that doctrinal lineage—proof that the right aircraft, flown by crews with judgment and courage, could crack open even the most dangerous valleys long enough for a hoist.

Relationships and Personal Character

Accounts by friends and colleagues describe Dengler as warm, meticulous, and generous with time—someone who combined artisan’s craft with aviator’s precision. His love of restoration flying—especially his Cessna 195—speaks to the tactile joy of mechanical systems working in harmony. Public talks often emphasized gratitude: for the crews who came looking, for the medical personnel who rebuilt his strength, and for the nation that gave him the chance to fly.

On Screen Versus On the Record

The documentary Little Dieter Needs to Fly remains the closest screen account to Dengler’s voice—focused on memory, detail, and moral tone. Rescue Dawn takes dramatic license, compressing timelines and character arcs for narrative momentum. Readers seeking the most accurate reconstruction should consult Dengler’s memoir and award citations, then use film as an interpretive layer rather than an archival substitute.

The A‑1 Skyraider in Context: International Service and Legacy

Understanding Dengler's story also means understanding the A‑1. Built around reliability, payload, and endurance, the Skyraider could linger over downed crews for hours, put ordnance precisely, and absorb battle damage that would cripple lighter jets. In Southeast Asia, “Sandy” callsigns became synonymous with courage—A‑1 crews escorting rescue helicopters into hostile valleys and weather windows that closed as quickly as they opened. Dengler's own cockpit discipline—fuel planning, systems knowledge, and low‑altitude energy management—was part of that culture.

The book documents the Douglas Skyraider's aircraft history, including Royal Navy service and service in Sweden, providing comprehensive coverage of the aircraft's international significance. The Skyraider's Royal Navy service demonstrates its operational versatility and the recognition of its capabilities by international operators. The Swedish service, documented in the appendix with details of the Scottish Aviation Skyraider for Sweden, illustrates the aircraft's continued operational relevance and international deployment.

The Skyraider's design philosophy emphasized operational flexibility and reliability, characteristics that made it effective across diverse operational environments and mission requirements. Its piston engine configuration, while outdated compared to jet aircraft, provided advantages in endurance, low-speed handling, and operational simplicity that were crucial for missions requiring extended loiter time and precise ordnance delivery. These characteristics made the Skyraider uniquely suited for SAR escort and close air support missions during the Vietnam War period.

The aircraft's exceptional payload capacity enabled it to carry diverse ordnance loads, from conventional bombs and rockets to specialized weapons for specific mission requirements. This versatility made the Skyraider effective across a wide range of operational scenarios, from interdiction missions to close air support and SAR escort. The aircraft's ability to operate effectively at low altitudes and in challenging weather conditions further enhanced its operational value during the Vietnam War period.

The Skyraider's legacy extends beyond its operational service to influence subsequent aircraft design and operational doctrine. The aircraft's operational success demonstrated the value of specialized design for specific mission requirements, illustrating how aircraft optimized for particular roles could achieve exceptional effectiveness. The lessons learned from Skyraider operations continue to influence modern aircraft design and operational employment, demonstrating the lasting significance of this remarkable aircraft.

Leadership and Survival Lessons

- Moral clarity under coercion: His refusal to sign propaganda had real costs but preserved group cohesion and personal agency.

- Preparation and craft: Small skills—improvised tools, knots, lock awareness, foot care, water discipline—compound under pressure.

- Observation before action: He studied guard patterns, terrain, and weather before committing to an escape window.

- Team dynamics: Sharing knowledge across prisoners increased everyone’s odds; shared purpose countered despair.

- Signal plan: Pre‑planned signaling materials and contrast thinking (fabric, smoke, cleared brush) were decisive in rescue.

Selected Timeline

- 1938: Born in Wildberg, Württemberg, Germany (22 May).

- 1956: Emigrates to the United States.

- 1957: Enlists in the U.S. Air Force; later studies aeronautics in California.

- Early 1960s: Earns Navy wings; qualifies in the A‑1 Skyraider; joins VA‑145.

- Dec 1965: Deploys aboard USS Ranger to Western Pacific.

- 1 Feb 1966: Shot down over Laos; captured.

- 29 Jun 1966: Escape from a Laotian prison camp.

- July 1966: Sighted by U.S. aircraft; rescued by SAR forces.

- Late 1960s: Returns to flying; later transitions to airline and test piloting.

- 1977: Returns to Laos to visit former camp area.

- 2001: Dies in California (7 Feb); interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Principal Sources and Further Reading

For comprehensive coverage of Dieter Dengler's life and achievements, explore these authoritative works by Charles E. MacKay:

- Dieter Dengler, Skyraider 04 Down, the Man the Ship the Plane — The definitive 102-page biography describing the life and times of the American Hero Dieter Dengler, including the history of the USS Ranger and her deployments off Vietnam, comprehensive coverage of the Douglas Skyraider aircraft history with Royal Navy service and service in Sweden, and a thrilling account of his capture, imprisonment and escape based on CIA reports

- Soaring With Wings: Percy Pilcher Wants To Fly — Companion volume exploring early aviation pioneering, creating a connection between remarkable aviation stories across different eras

Additional sources include Dieter Dengler's own memoir, Escape from Laos, Bruce Henderson's Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam War, which contextualizes the biography with interviews and archival work. Werner Herzog's Little Dieter Needs to Fly (documentary, 1997) offers a deeply personal portrait, which he later dramatized in Rescue Dawn (2006). These works, alongside official citations and unit histories, form a coherent record when read together, helping separate dramatic embellishment from the sober, documented timeline.

U.S. Navy award citations and unit histories (VA‑145; USS Ranger deployments) provide authoritative documentation of Dengler's service and achievements. U.S. Air Force SAR accounts regarding 1966 Laos rescues and "Sandy" doctrine provide insights into the rescue operations that recovered Dengler and the operational procedures that made these rescues possible.

Note on sources: exact unit identifiers and sequences for the initial sighting and helicopter hoist can vary by account across official histories and memoir literature. This narrative follows the broad areas of agreement while avoiding contested micro‑details not settled by primary documentation. The book's use of CIA reports ensures that the account of capture, imprisonment and escape is grounded in authoritative intelligence documentation, providing reliable factual foundation for understanding Dengler's experience.

Academic Recognition and Research Value

The book represents comprehensive original research documenting Dengler's life and achievements. The 102-page A5 format provides detailed coverage while remaining accessible to general readers. The book's comprehensive documentation of USS Ranger operations, Skyraider aircraft history, and Dengler's escape based on CIA reports ensures that this remarkable story is preserved with factual accuracy and historical rigor.

The book's value extends beyond individual biography to provide insights into carrier aviation operations, aircraft development, and POW operations during the Vietnam War. The comprehensive coverage of USS Ranger deployments and Skyraider operations provides valuable context for understanding naval aviation during this crucial period. The documentation of the Skyraider's international service, including Royal Navy and Swedish operations, demonstrates the aircraft's global significance and operational versatility.

The book's companion relationship to the Percy Pilcher biography creates an interesting connection between remarkable aviation stories, demonstrating how aviation achievement spans different eras and contexts. This connection illustrates the continuity of aviation achievement and the human determination that characterizes aviation progress across different historical periods.

References

- Royal Air Force Museum — Aircraft Collection — Royal Air Force Museum

- Imperial War Museums — Aviation History Articles — Imperial War Museums

- FlightGlobal Archive — FlightGlobal