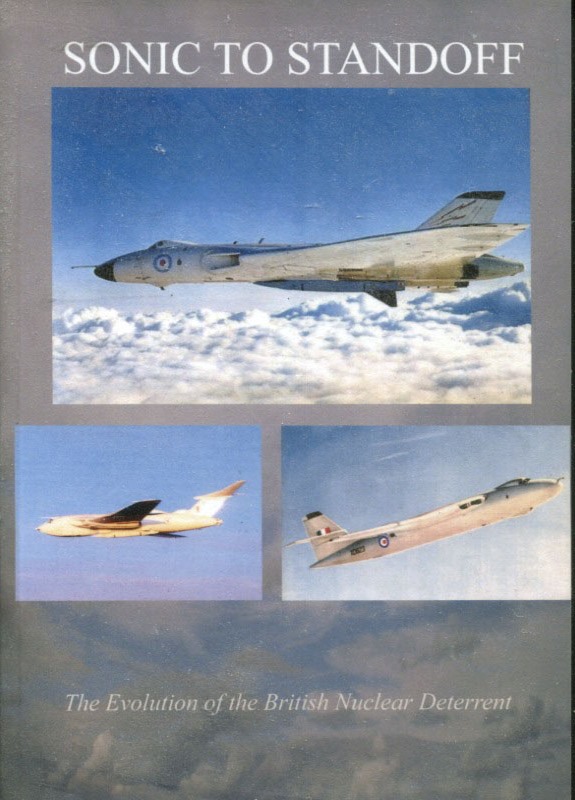

Supersonic point‑defence in British skies: the Lightning’s climb and dash defined QRA for a generation.

Introduction: Britain’s Supersonic Interceptor

The English Electric Lightning was the Royal Air Force’s definitive point‑defence interceptor of the Cold War — a twin‑Avon, Mach‑2, steep‑climbing thoroughbred designed to get airborne fast, climb vertically, acquire with AI.23 AIRPASS radar, and deliver a missile kill against high‑speed intruders long before they reached Britain’s targets. Its story is about systems thinking as much as speed: a design pathway from the experimental P.1A through the production F.1 to the range‑extended F.6; an operational doctrine built around Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) scrambles; and a maintenance culture that kept an exceptionally high‑performance aircraft serviceable under British weather, day and night.

Lightning F.6 in full reheat: stacked Avons, small wing, and slender fuselage prioritised climb and dash over endurance.

Origins and Research Lineage: From P.1 to Lightning

The Lightning’s origins lie in English Electric’s research into high‑speed aerodynamics and compact, high‑thrust installations. The experimental P.1A made its first flight in 1954, demonstrating the viability of a highly swept wing, ventral intake, and vertically stacked engines. The P.1B, flying in 1957, introduced afterburning Rolls‑Royce Avons and systems closer to production. The Lightning F.1 entered RAF service in 1960 with No. 74 Squadron at Coltishall, inaugurating a QRA era in which scramble‑to‑intercept times were measured in single minutes.

While W.E.W. “Teddy” Petter’s leadership at English Electric shaped the company’s fighter culture, the Lightning programme’s production design maturity is identified with Frederick Page and colleagues who refined structure, systems, and maintainability. The programme transitioned to the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) amid industry consolidation, but the aircraft retained the English Electric identity in popular memory — a testament to the P.1 lineage.

Configuration: Stacked Engines, Small Wing, and Intake Geometry

The Lightning’s signature innovation is its vertically stacked Rolls‑Royce Avons within a tight fuselage, fed by a circular ventral intake with a translating shock cone. Stacking shortened ducting, reduced frontal area, and concentrated mass near the centreline, yielding outstanding pitch response and a thrust line aligned with the aerodynamic centre. The wing — relatively small in area with high sweep — minimised drag at supersonic speeds and, together with powerful tail surfaces, gave the aircraft precise, fighter‑like handling.

Trade‑offs were explicit. The compact intake and small wing favoured climb and dash but constrained fuel volume. Early marks had limited endurance, addressed progressively by belly tanks, over‑wing tanks, and airframe refinements on the F.6. The engineering philosophy was clear: achieve intercept geometry quickly; endurance could be managed by basing, tanker support (where available), and procedural economy in climb and cruise.

Ventral intake with translating cone: shock management for supersonic flow and compact radar/duct installation.

Powerplant and Systems: Avon and AIRPASS

Successive Rolls‑Royce Avon variants equipped the Lightning series, delivering reliable thrust and strong acceleration into reheat. The avionics core was the Ferranti AI.23 AIRPASS radar, a pioneering lead‑computing interception aid integrated with the pilot’s sighting system. Early armament combined 30 mm Aden cannon with de Havilland Firestreak infrared missiles; later marks replaced Firestreak with the more capable Red Top, optimised for higher off‑boresight and supersonic envelopes.

- Engines: Rolls‑Royce Avon (Mk 200‑series in later marks), afterburning; vertically stacked, with independent systems and fire protection.

- Radar: Ferranti AI.23 AIRPASS; search, track, and ranging functions supporting missile/visual intercepts in day/night and marginal weather.

- Armament: 2× IR missiles (Firestreak → Red Top), 2× 30 mm Aden cannon (varied by mark/fit), centreline/belly tank for range on later marks.

- Fuel: internal fuselage/wing volume supplemented by large ventral tank (F.3/F.6) and optional over‑wing tanks for ferry/range extension.

Flight Qualities and Performance

Pilots valued the Lightning’s phenomenal climb, roll, and acceleration. Reheat take‑off followed by near‑vertical climb to altitude compressed the intercept timeline dramatically. The thin wing and high wing loading made the aircraft a stable gun/missile platform at speed, with crisp control response. The costs were short endurance and exacting energy management at low speeds, mitigated by disciplined circuit procedures and precise approach handling.

“From brakes‑off to angels forty in minutes — the Lightning was a rocket with a cockpit. It demanded respect on fuel, but nothing got to the intercept point faster.”

Marks and Evolution

- F.1 / F.1A: Initial service marks (1960 onward) with Firestreak and early AI.23; seminal QRA experience and tactics development.

- F.2 / F.2A: Systems refinements, reliability improvements, and airframe updates extending capability and maintainability.

- F.3: More powerful Avons and revised systems; missile‑centric fit moving gun armament off some frontline examples.

- F.6: Definitive RAF mark — larger belly tank, extended fin and cambered wing leading edge for better low‑speed characteristics, Red Top missiles, and optional over‑wing tanks for range.

- Export (T.55/F.53): Two‑seat trainers and multi‑role variants delivered to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait with role flexibility beyond pure interception.

QRA posture: covers off, ladders fitted, carts plugged — minutes from call to airborne in all weathers.

Operations: QRA, Intercepts, and Northern Air Defence

Lightning squadrons formed the backbone of Britain’s air defence into the 1970s. Typical profiles involved klaxon‑driven scrambles from dispersal, rapid reheat climb to a radar‑guided rendezvous, and handover to onboard AI.23 for terminal guidance. Intercepts of Soviet Tu‑95 “Bear” and maritime reconnaissance types over the North Sea became routine illustrations of deterrence and professionalism. Photographs of Lightnings formating alongside Bears — cameras visible in the Bear’s windows — capture a distinctive Cold War theatre.

Weather and sea states added complexity. Icing, low cloud, and night operations tested pilots and ground crews alike. The aircraft’s short legs required tight coordination between ground control, tanker availability (where planned), and prudent throttle management in the climb and on return to base. Engineering teams honed turn‑round procedures, inspecting access panels, reheat plumbing, and missile readiness with brisk precision.

Maintenance, Reliability, and Turn‑round

Sustaining a Mach‑2 interceptor on QRA demanded exacting maintenance culture. The stacked engine layout simplified some access runs but packed systems densely. Line crews monitored hot section health, reheat seals, and intake cone rigging; radar technicians kept AI.23 calibrated in Britain’s variable climate. Scheduled servicing balanced fatigue tracking and corrosion control with the operational imperative to keep pairs on readiness.

Comparative Context: Mirage III, F‑104, F‑106

Contemporaries reveal the Lightning’s niche. The Dassault Mirage III excelled in simplicity and export‑friendly multirole utility; the Lockheed F‑104 Starfighter prioritised dash speed and altitude with even less wing and comparable endurance constraints; the Convair F‑106 Delta Dart integrated powerful radar and missile systems for continental defence. The Lightning’s distinctive proposition was reaction time and climb in a compact national airspace — a point‑defence purist’s machine optimised for Britain’s geography and threat model.

Comparative context: design choices reflect mission and geography — each type optimised a different slice of the interceptor problem.

Exports and Later Service

Lightning exports to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait extended the type’s life and broadened its role set. The F.53 introduced limited ground‑attack capability and reconnaissance fits while preserving the core interception performance. Trainer variants (T.4/T.5/T.55) sustained pilot conversion and proficiency with dual controls while reflecting the handling discipline required by the type.

Legacy, Preservation, and Modern Memory

Retired from RAF service in the late 1980s, the Lightning remains a living symbol of Cold War air defence. Museum examples across Britain (including airworthy‑taxiable specimens) preserve systems knowledge and awe the public with “fast taxi” demonstrations that still shake the ground. For a period, civilian operation in South Africa showcased limited private flying; subsequent safety reviews ended these activities but confirmed enduring public fascination.

Technically, the Lightning’s lessons endure: tightly integrated propulsion/airframe design; honest acknowledgment of endurance constraints traded for climb and speed; and the value of a doctrinally coherent weapons system built around geography and QRA realities. Modern quick‑reaction aircraft retain the same imperatives of readiness, climb, and sensor‑weapon integration — now with the fuel fraction that the Lightning’s compact form could not accommodate.

Selected Technical Notes

- Powerplant (typical later marks): 2× Rolls‑Royce Avon afterburning turbojets (Mk 301/302 family).

- Performance: Mach 2+ class; exceptional initial rate of climb; service ceiling in excess of 50,000 ft for intercept geometry.

- Radar/Weapons: AI.23 AIRPASS with Firestreak transitioning to Red Top; mixed cannon fits by mark.

- Fuel/Range: Increased by large ventral tank (F.6) and optional over‑wing tanks; endurance remained the type’s primary limitation.

Further Reading and Related Works

- Captain Eric Brown: Test Pilot Extraordinary — professional evaluations that frame supersonic handling and systems.

- Lightning Development — programme milestones and mark‑by‑mark evolution.

- Jet‑Age Cold War Development — broader context of British and Allied interceptor doctrine.

Conclusion

As an integrated weapons system built for Britain’s QRA mission, the Lightning succeeded brilliantly: it got airborne fast, climbed hard, and met targets at altitude with reliable sensors and effective missiles. Its limitations were understood and managed; its strengths deterred and impressed. The type’s reputation — a pilot’s machine with rocket‑ship performance — rests on engineering that was honest about trade‑offs and uncompromising about the mission that mattered.