From salt spray to thin sections: racing knowledge that shaped British fighters.

Introduction: Speed, Science, and National Pride

The Schneider Trophy contests (1913–1931) transformed seaplane racing into a crucible of engineering where aerodynamics, engines, and operations were pushed to their practical limits. Britain’s ultimate retention of the Trophy in 1931 — achieved by Supermarine’s S.6B powered by the Rolls‑Royce R — was more than a sporting victory: it was a nationally orchestrated research programme whose lessons flowed directly into pre‑war and wartime combat aircraft. This Enhanced Edition presents a formal, evidence‑based account of the technology, people, and organisations behind the record books — and explains precisely how thin radiators, high‑boost fuels, and integrated systems engineering turned salt‑spray competition into national preparedness.

What the Rules Drove: Water Operations as Design Constraint

Unlike landplanes, Schneider racers had to take off and alight on water, complete turns around a marked course, and survive sea states and spray. These requirements forced a set of design trade‑offs that would shape every successful entrant: floats with a clean step for rapid unsticking; spray management to protect intakes and propellers; and structures resilient to repetitive slamming loads. The rules therefore did not merely reward speed — they rewarded robust speed delivered through integrated solutions.

Powerplant at the Limit: Rolls‑Royce R Development

The Rolls‑Royce R engine, a supercharged V‑12 derived from contemporary Merlin precursors, was engineered specifically for unprecedented specific output. Achieving this demanded:

- High boost pressures with precise mixture control across short, intense runs.

- Tailored fuel formulations (benzole blends; anti‑knock agents) to delay detonation at elevated cylinder pressures.

- Cooling strategies that combined surface/evaporative radiators and tightly managed oil circuits.

- Rigorous instrumentation: thermocouples, pressure taps, and calibrated gauges to keep every parameter inside a narrow band.

Cooling was not an afterthought; it was the limiting factor. The engineering challenge lay in shedding vast heat loads without ruinous drag. This demanded thin, flush radiators, careful ducting, and flight profiles that balanced speed with thermal margins. The discipline established here would later inform Merlin installation practices in the Spitfire and other frontline types.

Aerodynamics: Thin Sections, Cooling Drag, and Interference Control

R. J. Mitchell’s design team refined thin wing sections and fairings to reduce form and interference drag. The floats, struts, and fuselage junctions were shaped not only for structural efficiency but to minimise vortex‑rich interference fields. Evaporative and surface radiators turned parts of the airframe into distributed heat exchangers, reducing radiator frontal area at the cost of exacting manufacturing and maintenance discipline. The resulting aircraft were exercises in drag bookkeeping: every inch of surface did double duty, either carrying load or shedding heat — and often both.

Hydrodynamics and Float Dynamics

Float geometry governed take‑off run, spray, and directional stability. The step had to be placed to break suction at the correct speed; chines and spray rails kept water away from the propeller and intakes. The float‑to‑fuselage strut system balanced stiffness (to prevent flutter and shimmy) with weight; any excess mass would cascade into reduced acceleration and higher take‑off speeds. Water handling tests were as critical as wind‑tunnel trials, because small hydrodynamic misjudgements could stall a programme irrespective of engine power.

Operations: Course, Weather, and Turn Technique

Record attempts were flown around multi‑leg courses with exacting timing and barograph verification. Pilots trained to execute sustained high‑G turns that placed unique thermal and lubrication demands on the engine; fuel slosh and temporary starvation had to be anticipated and engineered out. Weather added a second layer of risk: sea state, wind shear near the surface, and salt deposition on radiators all influenced whether a record could be credibly attempted on a given day.

Organisation and Patronage: How Britain Won in 1931

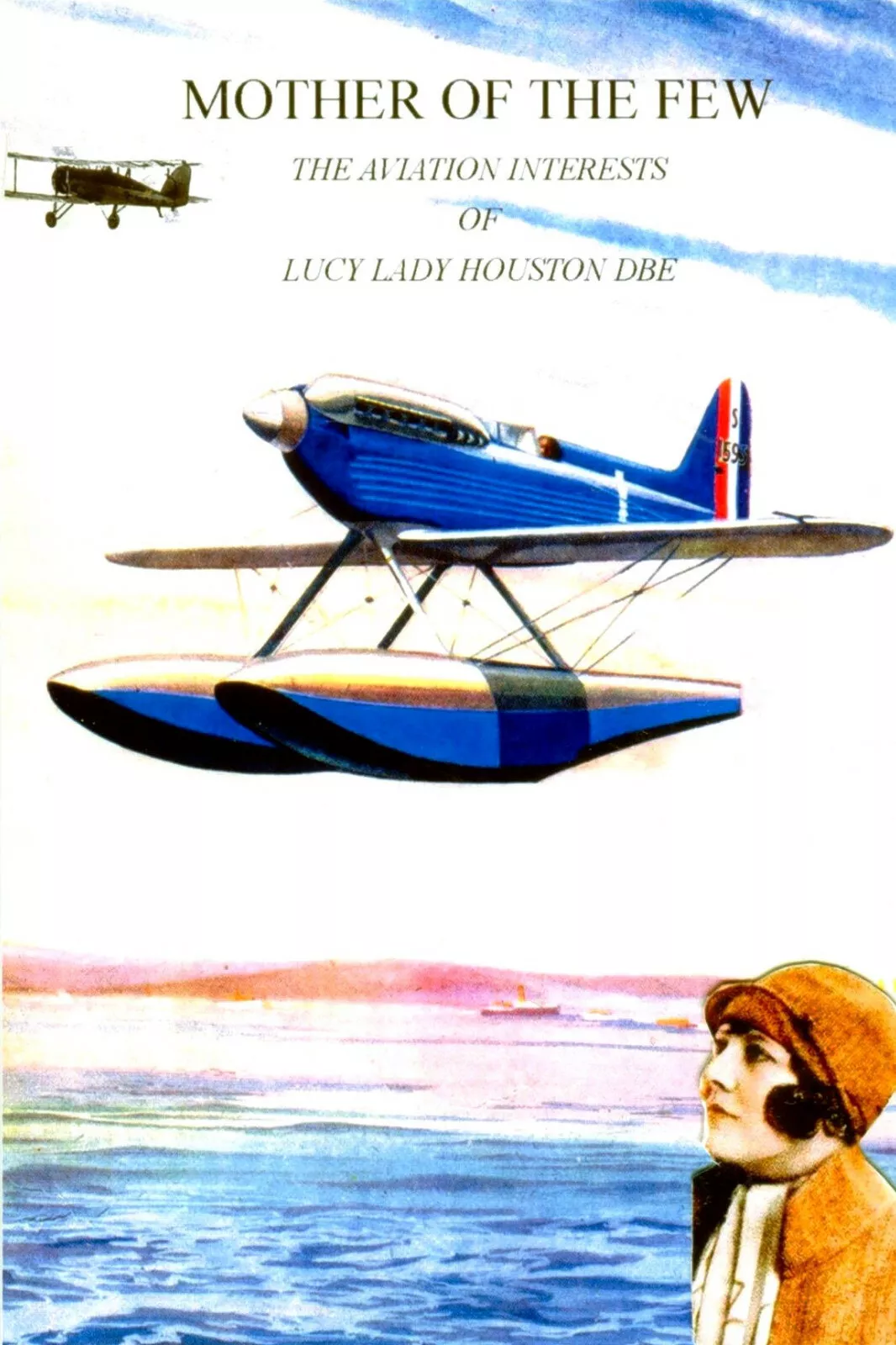

Britain’s 1931 success was organisational as much as technical. The Air Ministry provided institutional support; Supermarine provided design leadership; Rolls‑Royce delivered powerplant breakthroughs; RAF pilots brought disciplined flight test and course technique. When government funds ran short, Lady Lucy Houston’s £100,000 patronage bridged the gap, preserving programme momentum. This public‑private partnership anticipated the rapid industrial mobilisation of the later 1930s — a template where prototype racing informed national rearmament.

Pilots and Test Discipline

Pilots trained to treat the aircraft as an instrumented laboratory. Boost settings, mixture control, coolant flap positions, and climb/turn profiles were rehearsed repeatedly before any official attempt. Debriefs relied on data — temperature strips, barograph traces, and refuelling logs — not anecdote. The culture of data‑driven iteration, rare in sport, became the norm in British programme management on the eve of war.

Record Runs and Verification

Official records required redundant timing, calibrated barographs, and approved observers. The S.6B’s 400+ mph achievements were therefore not claims but measured results. These procedures mattered because they shaped procurement confidence. When, in the late 1930s, manufacturers proposed fighter performance envelopes, decision‑makers already had a mental model for what verified data looked like — thanks to a decade of Schneider discipline.

From Schneider to Spitfire: Technical Throughlines

Direct technical continuities included: thin, efficient wing and tail sections; low‑drag radiator philosophy that matured into Meredith‑effect installations; assumptions about reliable high‑boost engines; and a culture of fit, finish, and measurement that carried into wartime factories. The Spitfire was not a copy of any racer — its mission was different — but it inherited the racer’s refusal to accept avoidable drag or unmanaged heat.

Manufacturing and Materials

Racers demanded machining and surface finishes beyond routine production standards: flush rivets, faired joints, and exact radiator tolerances. These practices seeded production methods in British factories, raising expectations for what could be achieved at scale when the war demanded it. Tooling, jigs, and inspection protocols borrowed liberally from racing practice, compressing the learning curve for combat aircraft.

Fuel Chemistry and Engine Life

Fuel blends used in record attempts were not identical to service fuels, but the learning around anti‑knock behaviour, mixture distribution, and spark characteristics fed straight into Merlin development. Equally, the brutal wear observed in racing — detonation scars, heat‑affected zones — taught designers where margins had to be widened for combat reliability. Racing thus offered a “fast‑forward” on degradation mechanisms that would otherwise take years to discover.

Safety, Risk, and Programme Governance

The programmes faced serious risks: engine bursts, structural failures in chop, and pilot workload at the edge of endurance. Britain’s 1931 effort succeeded because governance recognised risk honestly and reduced it methodically: pre‑run checklists, abort criteria based on temperature rates rather than absolutes, and a culture that privileged airworthiness decisions over publicity schedules. This approach, later mainstream in RAF operations, has roots in the Trophy era.

International Rivalry and Knowledge Flow

Italy and the United States fielded formidable teams, with Macchi and Curtiss pushing airframe and engine envelopes in parallel with Britain. Competition accelerated knowledge flow: public records and visible design choices cross‑pollinated; engineers studied each other’s float geometry, cooling concepts, and engine cowls. Far from a closed shop, the Trophy became a semi‑open technology exchange where national advantages were earned but not hidden from view.

Public Perception and Political Support

Press coverage framed racers as national symbols. The public saw numbers — “400 mph” — but the Air Ministry and Treasury saw validated processes, supplier networks, and project management under pressure. The political narrative — private patronage unlocking public benefit — helped justify research spending in the fraught budgets of the early 1930s.

Engineering Lessons to Carry Forward

- Treat cooling as core aerodynamics: every square inch must earn its place.

- Integrate fuels, engines, and airframes from day one: performance comes from systems, not parts.

- Instrument and iterate: measure, adjust, and only then attempt records or capability claims.

- Organise across boundaries: patrons, services, and industry each contribute distinct capabilities.

Further Reading and Related Works

- Lady Lucy Houston — the patron whose intervention preserved Britain’s 1931 bid.

- Supermarine Spitfire Development — Schneider lessons in wartime guise.

- Mother of the Few — an authoritative account of funding and national will.

Conclusion

The Schneider Trophy era proved that racing at the edge is disciplined research in disguise. Britain’s 1931 triumph distilled a national collaboration — design offices, factories, service pilots, and private patrons — whose dividends were realised when war came. The technical throughlines from S.6B to Spitfire are not marketing flourish; they are the measurable product of a culture that measured, learned, and engineered heat and drag as carefully as speed itself.

References

- Royal Air Force Museum — Aircraft Collection — Royal Air Force Museum

- Imperial War Museums — Aviation History Articles — Imperial War Museums

- FlightGlobal Archive — FlightGlobal