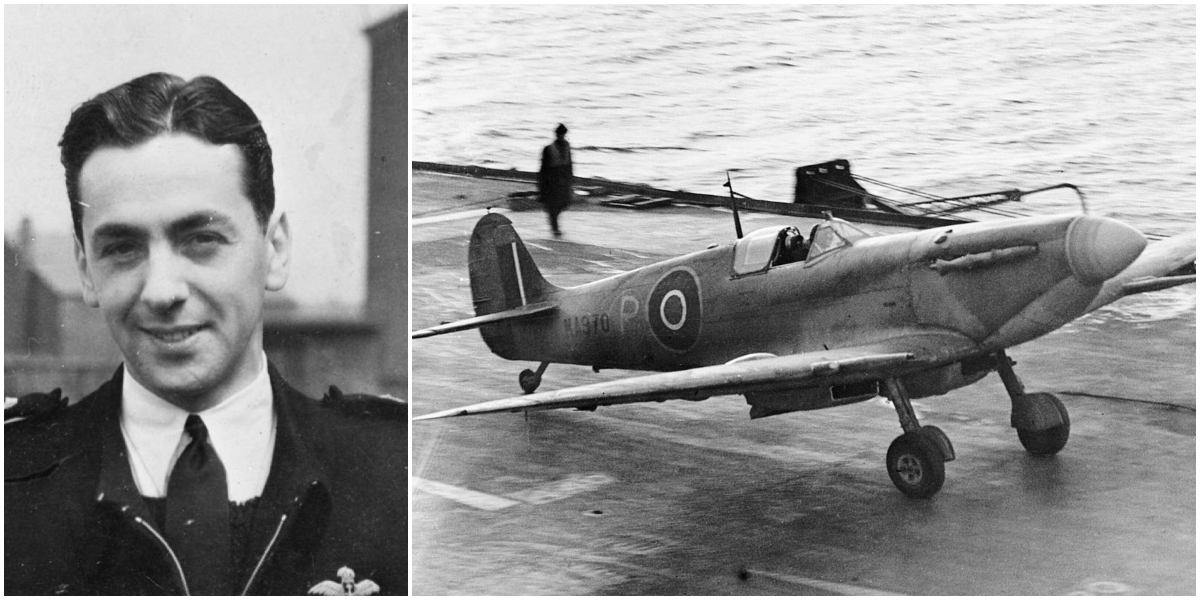

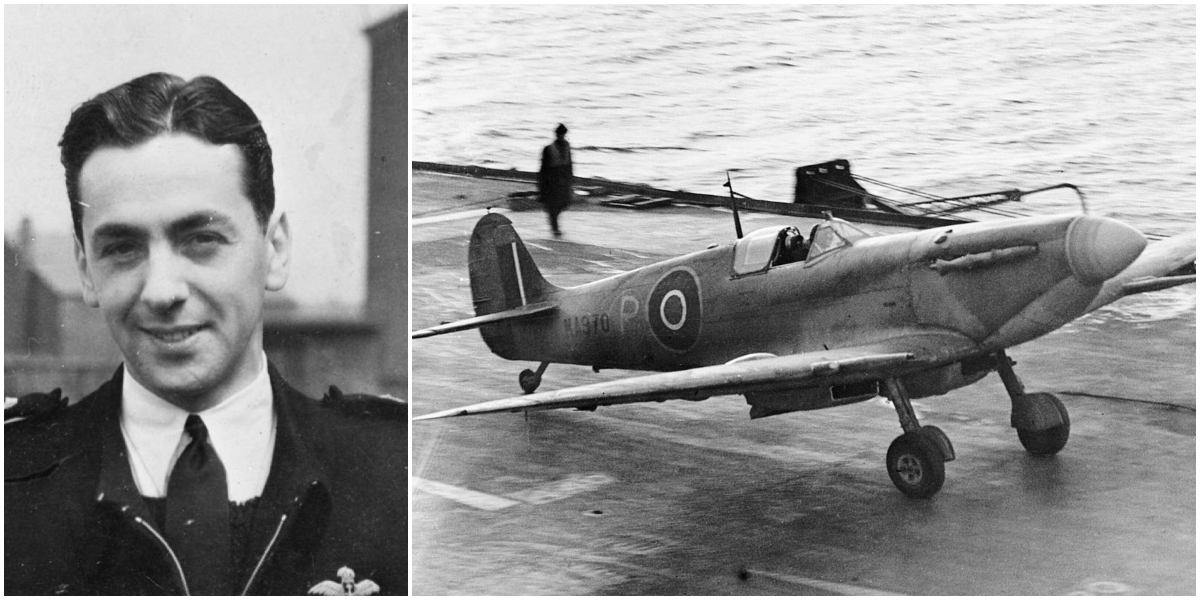

Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown (photograph).

Introduction: Precision at the Edge of Flight

Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown’s career places him alone in the annals of aviation testing. He flew more distinct aircraft types than any pilot on record, performed a record number of carrier landings, evaluated captured enemy aircraft at the end of the Second World War, and then bridged into the jet and early rotorcraft eras with the same blend of discipline and curiosity that made his reports foundational. The superlatives endure because they are anchored in method: Brown’s hallmark was rigorous observation, faithful adherence to procedure, and a willingness to translate risk into knowledge without romance or bravado.

Brown's achievements extend far beyond mere numbers. He made the first jet landing on an aircraft carrier and evaluated an exceptional range of captured enemy aircraft, including the Messerschmitt Me 163 rocket fighter and Me 262 jet, as well as numerous piston types. His carrier landing record of 2,407 arrested landings — including trials in demanding conditions — demonstrates a standard of skill joined to method.

From testing captured German jets to advancing helicopter operations aboard ships, Brown's career touched nearly every domain of flight in the mid‑twentieth century. His detailed reports and disciplined approach to experimental flying contributed measurably to aviation safety, carrier aviation doctrine, and the transition from piston to jet operations at sea.

Early Years and Wartime Foundations

Brown’s wartime foundation combined operational flying with increasingly specialized test duties. Selected for evaluation work on enemy aircraft late in the Second World War, he moved from the comfortable rituals of familiar types into the blunt reality of incomplete manuals, uncertain maintenance, and unknown handling. It was here that Brown refined the habits that would define his career: incremental envelope exploration, scrupulous note‑taking, and a relentless focus on what could be measured rather than what could be assumed.

Introduction: Precision at the Edge of Flight

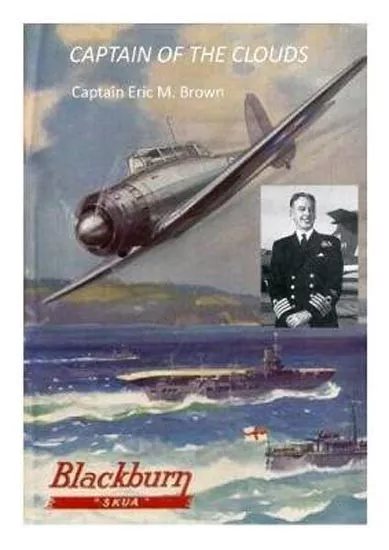

Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown's career places him alone in the annals of aviation testing. He flew more distinct aircraft types than any pilot on record, performed a record number of carrier landings, evaluated captured enemy aircraft at the end of the Second World War, and then bridged into the jet and early rotorcraft eras with the same blend of discipline and curiosity that made his reports foundational. The superlatives endure because they are anchored in method: Brown's hallmark was rigorous observation, faithful adherence to procedure, and a willingness to translate risk into knowledge without romance or bravado. Based on comprehensive research documented in Charles E. MacKay's authoritative biography Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown, Captain of the Clouds, Test Pilot: A Biography, this analysis presents the complete story of the world's most experienced test pilot and his extraordinary contributions to aviation.

Brown's achievements extend far beyond mere numbers. He made the first jet landing on an aircraft carrier and evaluated an exceptional range of captured enemy aircraft, including the Messerschmitt Me 163 rocket fighter and Me 262 jet, as well as numerous piston types. His carrier landing record of 2,407 arrested landings — including trials in demanding conditions — demonstrates a standard of skill joined to method.

The book provides background information on the flying life of the world's premiere test pilot, from his escapades in pre-war Germany to flying the Me 163 Komet. This illustrated booklet is a mine of information, documenting Brown's remarkable career from its earliest foundations through his most challenging test flights. The comprehensive coverage ensures that Brown's achievements are properly understood within the context of his complete career.

From testing captured German jets to advancing helicopter operations aboard ships, Brown's career touched nearly every domain of flight in the mid‑twentieth century. His detailed reports and disciplined approach to experimental flying contributed measurably to aviation safety, carrier aviation doctrine, and the transition from piston to jet operations at sea.

Early Years and Wartime Foundations

Brown's wartime foundation combined operational flying with increasingly specialized test duties. Selected for evaluation work on enemy aircraft late in the Second World War, he moved from the comfortable rituals of familiar types into the blunt reality of incomplete manuals, uncertain maintenance, and unknown handling. It was here that Brown refined the habits that would define his career: incremental envelope exploration, scrupulous note‑taking, and a relentless focus on what could be measured rather than what could be assumed.

The book documents Brown's escapades in pre-war Germany, providing context for understanding how his early experiences shaped his later achievements. These formative experiences established the foundation for his remarkable career, demonstrating how personal determination and skill development contributed to his eventual status as the world's most experienced test pilot. The documentation of these early years ensures that Brown's complete career trajectory is properly understood.

Steam Catapult Innovation and Carrier Aviation

The book explains Brown's involvement with the invention of the Steam Catapult for aircraft carriers and its success in the US Navy. There is a rare drawing of the steam catapult included, providing valuable visual documentation of this crucial innovation. The steam catapult revolutionized carrier operations, enabling heavier aircraft to operate from carriers and significantly expanding carrier aviation capabilities. Brown's involvement in this development demonstrates his contributions to carrier aviation technology beyond piloting expertise.

The steam catapult's development addressed the fundamental challenge of launching heavier aircraft from limited carrier deck space. Brown's participation in this innovation demonstrates how test pilots contributed to technical development, not merely evaluating existing systems but participating in the creation of new solutions. The steam catapult's success in the US Navy validated the innovation's effectiveness and demonstrated its value for modern carrier operations.

For comprehensive coverage of carrier aviation history and the development of carrier technology, see Aircraft Carrier - Beardmore's HMS Argus, which provides detailed analysis of the world's first true aircraft carrier and the evolution of carrier operations. Brown's service on HMS Argus, documented in the book, connects his career to this foundational carrier development.

The book includes Brown's lecture on Carrier Aviation to the United States Navy, supported with rare illustrations. This lecture demonstrates Brown's role as an instructor and knowledge transfer specialist, sharing British carrier aviation expertise with international partners. The lecture's inclusion in the book ensures that Brown's instructional contributions are properly documented and preserved.

HMS Argus Service and Training

The book documents how Winkle Brown flew off the carrier vessel, HMS Argus, a training post he disliked, and her story is here. HMS Argus was the world's first true aircraft carrier, built by Beardmore and converted from the liner Conte Rosso. Brown's service on HMS Argus provided crucial experience in carrier operations, establishing the foundation for his later achievements in carrier aviation testing. Despite his dislike for the training post, this experience proved invaluable for his subsequent career.

For comprehensive coverage of HMS Argus and its role in carrier aviation development, see HMS Argus: The World's First Aircraft Carrier, which provides detailed analysis of the carrier's design, construction, and operational history. Brown's service on HMS Argus represents one connection between his career and this foundational carrier development.

The book includes numerous black and white pictures including HMS Perseus and HMS Rocket out of Londonderry, documenting Brown's carrier service and the vessels on which he served. These photographs provide valuable visual documentation of Brown's operational context and the carriers that shaped his career. The comprehensive photographic coverage ensures that Brown's service is properly documented with visual evidence.

Carrier Jet Integration: Approach, Arrestment, and Energy

Brown’s jet carrier trials forced a re‑examination of approach cues. Piston fighters telegraphed energy through propeller wash and throttle response; early jets arrived quieter, with different spool dynamics and less immediate thrust response. Brown’s reports emphasized stabilized approaches at set attitudes and speeds, consistent sightlines to the deck, and disciplined throttle management to avoid low‑energy sink just before the wires. Arrestor‑hook geometry and wire tensions were part of the same system; where landing gear and hook loads revealed shortcomings, Brown’s notes traced cause to remedy without theatrical blame.

Key Technical Themes in Brown’s Carrier‑Jet Reports

- Stabilized Approaches: Fixed attitude and speed, sightline to the deck constant; avoid last‑second corrections.

- Throttle Management: Account for jet spool dynamics; preserve margin to counter sink near the round‑down.

- Hook/Wire System Behaviour: Treat gear, hook, and arrestor wires as one tuned system; record loads and bounce tendencies.

- Reference Cues: Improve visual landing aids and deck markings to standardize jet approaches at sea.

- Procedural Repeatability: Turn novel handling into doctrine through checklists and disciplined briefing/debriefing.

Selected Timeline of Milestones

- Wartime test and evaluation: Transition to evaluation of enemy types; foundation of method built on incremental envelope expansion.

- Jet carrier landing: First jet landing on an aircraft carrier; reports informing stabilized approach parameters and arrestment checks.

- Captured types: Systematic evaluations of rocket, jet, and piston aircraft informing Allied understanding of adversary design approaches.

- Rotorcraft at sea: Early helicopter shipboard trials; development of deck procedures and hand signals.

- Publications and instruction: Translation of frontline testing into training materials for pilots and engineers.

Carrier Approach Technique: Notes and Practice

Brown emphasized that safe carrier approaches by jets depended on holding a known attitude and speed, resisting the urge to chase the deck visually at the close. He recorded throttle response characteristics and recommended power settings that preserved energy margins through the round‑down, with hook contact occurring under control rather than in a sink. These notes influenced standardized sightlines and the later refinement of visual landing aids.

Safety Contributions and Accident Learning

Not every trial ended neatly. Brown's reports treat incidents as data rather than theatre, describing causality — whether in energy management, system tuning, or pilot cueing — and proposing specific changes. This habit turned individual risk into institutional memory, improving survivability for pilots who would follow his procedures rather than rediscover hazards.

Helicopter and Shipboard Trials

Brown's curiosity extended naturally to rotorcraft as they moved from novelty to utility. Early shipboard trials with helicopters required new deck procedures, new hand signals, and an appreciation for downwash and rotor wake on crowded decks. Brown recognized that success would come from the same formula proven elsewhere: steady control response, sightlines for hover cues, and checklists that converted demanding tasks into predictable operations.

The book includes pictures of Brown's Hoverfly flight through smoke clouds generated by a Fiesler Storch, documenting his helicopter evaluation work. This documented flight demonstrates Brown's comprehensive approach to testing, evaluating helicopter capabilities in challenging conditions and documenting performance characteristics. The Hoverfly evaluation work demonstrates how Brown's test pilot expertise extended across all aircraft types, from fixed-wing to rotary-wing aircraft.

For comprehensive coverage of helicopter development and the context within which Brown evaluated rotorcraft, see The Sycamore Seeds: The Early History of the Helicopter, which provides detailed analysis of British helicopter development. Brown's helicopter evaluation work contributed to the development of operational procedures and safety standards for rotorcraft operations.

Brown's helicopter trials established procedures and techniques that would become standard in naval helicopter operations. His systematic approach to evaluating helicopter handling characteristics, deck procedures, and operational capabilities contributed significantly to the development of naval helicopter doctrine. The documentation of this work ensures that Brown's contributions to helicopter development are properly recognized.

Books, Reports, and Teaching

Brown's writing style mirrored his cockpit discipline: exact, unembellished, and focused on what a pilot must do. His published works and formal reports continue to be used in instruction for carrier operations and flight‑test methodology, preserving both the detail and the tone of a professional who valued clarity over anecdote.

The book includes valuable references to articles and books Brown published, ensuring that his written contributions are properly documented. These publications represent Brown's efforts to translate his test pilot experience into instructional materials and technical documentation that would benefit future generations of pilots and engineers. The comprehensive documentation of Brown's publications ensures that his written contributions are properly recognized and accessible.

Brown's lecture on Carrier Aviation to the United States Navy, included in the book and supported with rare illustrations, demonstrates his role as an instructor and knowledge transfer specialist. This lecture represents Brown's efforts to share British carrier aviation expertise with international partners, contributing to the development of carrier aviation doctrine worldwide. The lecture's inclusion ensures that Brown's instructional contributions are properly documented and preserved.

Brown's publications and lectures continue to influence carrier aviation training and operational procedures. His clear, precise writing style and focus on practical procedures have made his works essential references for pilots and engineers involved in carrier operations. The lasting influence of his written contributions demonstrates the value of his disciplined approach to documentation and knowledge transfer.

Academic Recognition and Research Value

The book represents comprehensive original research documenting Brown's life and achievements. The over 50-page A5 format provides detailed coverage while remaining accessible to general readers. The book's comprehensive documentation of Brown's career, including his pre-war experiences, wartime test work, steam catapult development, and carrier aviation contributions, ensures that this remarkable story is preserved with factual accuracy and historical rigor.

The book's value extends beyond individual biography to provide insights into test pilot techniques, carrier aviation development, and aircraft evaluation procedures. The comprehensive coverage of Brown's test pilot career and his contributions to carrier aviation provides valuable context for understanding aviation development during this crucial period. The documentation of Brown's work with captured enemy aircraft, steam catapult development, and carrier aviation instruction creates a comprehensive resource for understanding test pilot contributions to aviation progress.

The book's comprehensive photographic coverage, including numerous black and white pictures of HMS Perseus, HMS Rocket, Hoverfly flights, steam catapult drawings, and German aircraft images, ensures that Brown's career is properly documented with visual evidence. These photographs provide valuable insights into Brown's operational context and the aircraft and vessels that shaped his career. The comprehensive visual documentation contributes significantly to the book's value as a historical resource.

Pilot Accounts and Test Discipline

Brown’s published accounts are admired because they sound like his reports: careful, dispassionate, and detailed. Where he found vices, he named them; where virtues appeared, he explained how pilots might exploit them safely. He did not romanticize risk. His respect for procedure and frank discussion of failure modes turned personal courage into institutional learning — the only kind of bravery that lasts.

Comparisons and Contemporaries

Brown’s portfolio differs from contemporaries who are better known for supersonic milestones or single‑program breakthroughs. His achievement was breadth with depth: piston, jet, rocket, and rotorcraft, on land and at sea. In comparing records, one should keep roles in view. Brown’s unique value lay in converting risk across many types and environments into standardized, actionable doctrine. Others achieved singular speed or altitude; Brown built repeatable safety in places where the runway moved.

Enemy Aircraft Evaluations: Turning Risk into Data

Brown's evaluations of captured enemy types were not museum pieces in waiting; they were tools for understanding how the adversary thought about stability, systems, and pilot workload. He recorded cold starts, taxying, takeoff behavior, climb and acceleration, buffet cues, compressibility onset, stall progression, control harmony, and approach traits — always with an eye to reproducible notes. His work on rocket and jet types provided Allied engineers and tacticians with civil, unvarnished comparisons that improved training and counter‑tactics.

The book documents Brown's evaluation of German aircraft including the Dornier Jet and Focke Wulf etc., providing comprehensive coverage of his work with captured enemy types. The book includes drawings of the steam catapult and images of German aircraft, ensuring that Brown's evaluation work is properly documented with visual evidence. These evaluations provided crucial insights into German aviation technology and informed Allied understanding of enemy capabilities and design approaches.

Brown's evaluation of the Me 163 Komet rocket fighter represents one of his most challenging test flights. The book documents his experience flying this dangerous aircraft, demonstrating how Brown's methodical approach enabled safe evaluation of even the most challenging aircraft types. His evaluation reports provided valuable insights into rocket fighter performance and handling characteristics, informing Allied understanding of this advanced German technology.

For comprehensive coverage of German aircraft development and the context within which Brown evaluated captured types, see German Aircraft in the Great War 1914-1918, which provides foundational understanding of German aviation engineering traditions. The book's coverage of German aircraft development demonstrates how wartime requirements drove technical innovation and how post-war evaluation of these achievements informed subsequent Allied designs.

Brown's evaluation work extended beyond individual aircraft to encompass comprehensive analysis of German aviation technology and design philosophy. His systematic approach to evaluation ensured that valuable insights were captured and preserved for future use. The documentation of this evaluation work in the book ensures that Brown's contributions to understanding enemy technology are properly recognized and preserved.

Brown’s influence persists in curricula, shipboard procedures, and airworthiness standards. His writing — exact without being obscure — set a tone for flight‑test communication that valued clarity over drama. Carrier operations for jets and helicopters matured around the practices he helped articulate. The standards for sightlines, stabilized approach parameters, and arrestment checks did not appear fully formed; they were forged by pilots like Brown who documented what worked and what did not, and by engineers who listened.

Conclusion: Enduring Significance

Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown's career represents one of the most remarkable achievements in aviation history. His record of flying more aircraft types than any pilot in history, combined with his systematic approach to test flying and documentation, established standards that continue to influence aviation testing and carrier operations. Brown's contributions extend far beyond individual achievements to encompass carrier aviation development, aircraft evaluation procedures, and aviation safety improvements.

The comprehensive documentation provided in Charles E. MacKay's Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown, Captain of the Clouds, Test Pilot: A Biography ensures that this remarkable story is preserved for future generations. The book's thorough research, detailed illustrations, and careful documentation create an authoritative resource that does justice to Brown's achievements and contributions to aviation progress. This scholarly work ensures that the world's most experienced test pilot receives the recognition he deserves.

Brown's influence persists in curricula, shipboard procedures, and airworthiness standards. His writing — exact without being obscure — set a tone for flight‑test communication that valued clarity over drama. Carrier operations for jets and helicopters matured around the practices he helped articulate. The standards for sightlines, stabilized approach parameters, and arrestment checks did not appear fully formed; they were forged by pilots like Brown who documented what worked and what did not, and by engineers who listened.

Brown's legacy extends beyond individual achievements to influence broader aviation development. His test pilot techniques, carrier aviation procedures, and documentation methods contributed to subsequent aviation development and operational procedures. The fundamental principles demonstrated in Brown's work continue to influence aviation testing and carrier operations, demonstrating the lasting significance of these achievements.

Further Reading and Related Works

For comprehensive coverage of Captain Eric Brown's career and related topics, explore these authoritative works by Charles E. MacKay:

- Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown, Captain of the Clouds, Test Pilot: A Biography — The definitive biography providing background information on the flying life of the world's premiere test pilot, from his escapades in pre-war Germany to flying the Me 163 Komet, including his involvement with the invention of the Steam Catapult for aircraft carriers, his lecture on Carrier Aviation to the United States Navy, and comprehensive coverage of his service on HMS Argus, HMS Perseus, and HMS Rocket

- Aircraft Carrier - Beardmore's HMS Argus — Complete history of the world's first true aircraft carrier on which Brown served, providing context for understanding his carrier aviation experience

- HMS Argus: The World's First Aircraft Carrier — Detailed coverage of the carrier on which Brown served and its role in carrier aviation development

- Naval Aviation History: From Seaplanes to Supercarriers — Comprehensive analysis of carrier aviation evolution within which Brown's contributions occurred

- German Aircraft in the Great War 1914-1918 — Foundational understanding of German aviation engineering traditions that influenced the aircraft Brown evaluated

- The Sycamore Seeds: The Early History of the Helicopter — Coverage of helicopter development and the context within which Brown evaluated rotorcraft

Related Articles

- HMS Argus Operations: Pioneering Carrier Aviation Techniques — Operational procedures and techniques developed on the carrier where Brown served

- British Nuclear Deterrent: The V-Force and Cold War Strategy — Strategic context within which Brown's later test work occurred

- Helicopter Development Pioneers — Comprehensive coverage of rotorcraft development including Brown's helicopter evaluation work

References

- Royal Air Force Museum — Aircraft Collection — Royal Air Force Museum

- Imperial War Museums — Aviation History Articles — Imperial War Museums

- FlightGlobal Archive — FlightGlobal