Percy Pilcher: Scotland's Forgotten Aviation Pioneer - Expert analysis by Charles E. MacKay

Introduction: Scotland's Forgotten Aviation Pioneer

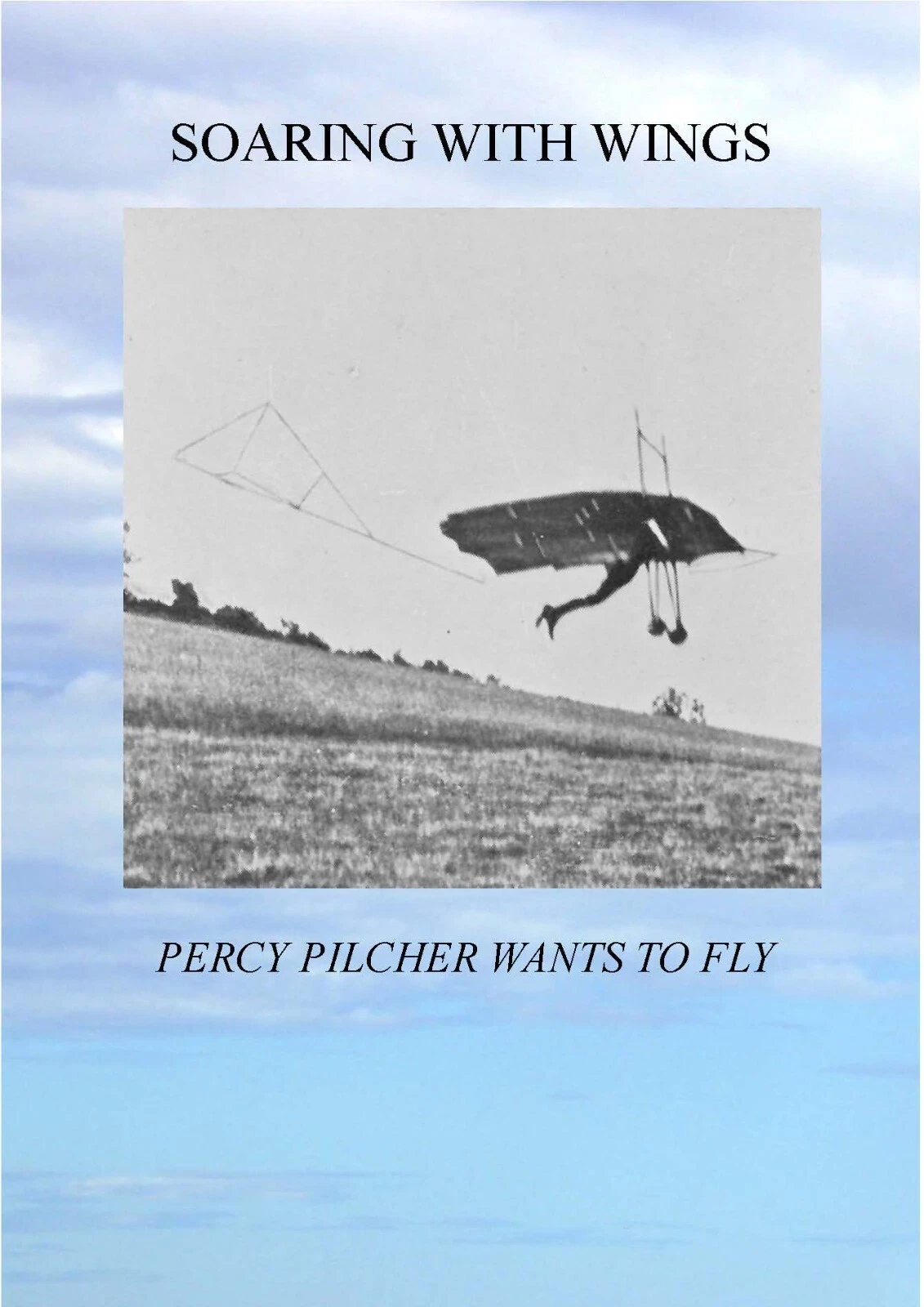

Percy Sinclair Pilcher (1866–1899) stands as Scotland's seminal pre‑Wright aviation pioneer. Trained as an engineer and influenced by continental gliding practice, Pilcher methodically iterated glider designs on Scottish fields throughout the late 1890s. His programme culminated in the celebrated Hawk glider and a practical plan for a lightweight engine installation. His untimely death in 1899 cut short a test campaign that, by informed historical assessment, had a plausible path to powered, sustained flight several years before Kitty Hawk. This comprehensive analysis is based on extensive research documented in Charles E. MacKay's authoritative biography Soaring with Wings: Percy Pilcher wants to Fly, a 171-page work profusely illustrated with many rare and interesting pictures and drawings that presents the definitive account of Pilcher's four years of experimental flying.

Scottish Industrial and Intellectual Context

Pilcher's work unfolded within a distinctive Scottish milieu: university engineering, model clubs, shipyard fabrication culture, and practical experiment. Glasgow and the west of Scotland, steeped in mechanical craft, provided both the tools and the habits of mind — measurement, rigour, iteration — that Pilcher applied to flight. He corresponded and cross‑pollinated with European pioneers (notably Lilienthal's published work), yet his programme was rooted in local sites, local weather, and a local community of hands‑on problem solvers. This Scottish context is comprehensively documented in Clydeside Aviation Volume One: The Great War, which covers the history of aviation on Clydeside from 1785 to 1919, including Pilcher's pioneering work.

The book describes Pilcher's flying at Auchensail, Wallaceton Cardross and in England, providing detailed accounts of his experimental work across different Scottish locations. There is a history of Cardross with a weather description for 1895 and 1896, which is crucial for understanding the environmental conditions that influenced Pilcher's glider development and testing schedules. These weather records demonstrate the practical challenges Pilcher faced and how he adapted his experimental programme to Scottish climate conditions.

Pilcher's position as assistant lecturer at Glasgow University provided access to engineering knowledge and facilities that supported his aviation experiments. The university environment connected him with Scotland's intellectual and industrial communities, creating a network of support for his pioneering work. His lectures at the University of Glasgow, some of which are described in the book, demonstrate his commitment to sharing knowledge and advancing aviation understanding within the academic community.

The Glider Programme: Bat → Beetle → Gull → Hawk

Pilcher's sequence of gliders exemplified sound engineering method: change one parameter at a time, instrument, observe, refine. The Bat explored structure and basic stability; the Beetle and Gull refined planform and bracing; the Hawk delivered controllable, repeatable flights of impressive distance for the 1890s. His bracing, tail volume choices, and pilot suspension solutions reflected iterative learning rather than one‑off tinkering.

The book provides comprehensive documentation of each glider in the series, describing the evolution from the Bat through to the celebrated Hawk. This progression demonstrates Pilcher's systematic approach to solving the fundamental problems of controlled flight. Each glider built upon lessons learned from previous designs, incorporating incremental improvements that refined stability, control, and structural efficiency.

The Hawk, which would ultimately kill him, represented the pinnacle of Pilcher's glider development. It demonstrated significant advances in controllability and structural design compared to his earlier gliders. The Hawk still exists today in Edinburgh, preserved as a testament to Pilcher's engineering achievements. This preservation ensures that future generations can study Pilcher's construction techniques and appreciate the sophistication of his design approach.

International Influences and Contacts

Pilcher's experimental work was profoundly influenced by Lilienthal, the great German aircraft pioneer, whom he met twice. These meetings provided crucial insights into glider design and flight techniques that shaped Pilcher's own experimental programme. The exchange of knowledge between Pilcher and Lilienthal represents one of the earliest examples of international collaboration in aviation development, demonstrating how pioneers shared discoveries despite geographical barriers.

Pilcher was also in contact with the Australian Hargrave and Octave Chanute in America, creating a network of correspondence that spanned three continents. This international exchange of ideas illustrates how aviation pioneers recognized the value of sharing knowledge and learning from each other's experiments. Chanute's work on glider design and Hargrave's contributions to aeronautical theory provided valuable perspectives that informed Pilcher's own developments.

Pilcher's employment by Hiram Maxim of Vickers machine-gun fame demonstrates his connection to Britain's industrial and engineering establishment. Maxim's work on powered flight experiments, while ultimately unsuccessful, provided Pilcher with valuable insights into propulsion systems and engine integration. This employment positioned Pilcher at the intersection of theoretical knowledge and practical engineering, enabling him to apply industrial techniques to aviation problems.

Perhaps most significantly, the Wright Brothers used Pilcher's data when constructing the Wright Flyer. This connection demonstrates Pilcher's influence on the eventual achievement of powered flight, even though he did not live to see it. The incorporation of Pilcher's research into the Wright Brothers' work illustrates the cumulative nature of aviation progress and Pilcher's important contribution to the foundation of powered flight.

Controls, Structure, and Materials

Control in the 1890s hinged on pilot weight‑shift and limited surface deflection. Pilcher's rigs combined triangulated wire bracing with wooden longerons and fabric covering. He experimented with tailplane area and incidence to balance longitudinal stability against climb responsiveness. Joints, turnbuckles, and fittings show an economy of mass without compromising integrity, revealing a mature appreciation of load paths consistent with the best contemporary practice.

Material selection aligned with available Scottish timber supplies and fittings available through engineering supply houses. Fabric tension, rib spacing, and spar depth followed practical rules of thumb refined by testing. The overall philosophy anticipated later formal stress analysis: prove the concept via flight envelopes, then strengthen where inspection reveals working or permanent set.

Pilcher's sister was instrumental in building the wings, demonstrating how family support and practical assistance enabled Pilcher's experimental work. This collaborative approach to construction illustrates the practical nature of early aviation development, where family members and local craftsmen contributed to building experimental aircraft. The detailed documentation of construction techniques provides valuable insights into early aviation manufacturing methods.

The structural design of Pilcher's gliders incorporated principles that would become standard in later aircraft construction. His use of triangulated bracing, efficient materials, and careful weight management demonstrated advanced understanding of structural engineering principles. These design choices enabled his gliders to achieve performance levels that were remarkable for the 1890s.

The Powered Flight Plan

Pilcher's notebooks and correspondence indicate a clear powering strategy: a compact, lightweight engine installation on the Hawk derivative, with attention to thrust line, propeller efficiency, and structural reinforcement around the engine mount. Weight budgeting was explicit. He targeted a power‑to‑weight ratio adequate for ground roll and low‑altitude climb in Scottish conditions, with an acceptance that initial flights would be straight‑ahead hops transitioning to longer circuits as control confidence improved.

The book documents Pilcher's plans for powered flight, revealing his systematic approach to solving the propulsion challenge. His calculations and design considerations demonstrate sophisticated understanding of the relationship between power, weight, and performance. This planning illustrates how close Pilcher came to achieving powered flight before his untimely death.

Pilcher's powered flight plan incorporated lessons learned from his glider experiments, particularly regarding structural requirements and control effectiveness. The transition from glider to powered aircraft represented a logical progression in his experimental programme, building upon proven glider designs while addressing the additional challenges of engine integration and propeller design.

Test Sites, Methods, and Safety

The book describes Pilcher's flying at Auchensail, Wallaceton Cardross and in England, providing detailed accounts of his experimental work across different locations. Open fields and modest slopes near Glasgow provided prevailing‑wind alignment and recovery room. Launch methods included towed starts and downhill run‑offs; spotters and assistants managed lines and stabilised the glider in gusts. Pilcher normalised inspection routines between flights — checking tension, fabric condition, fittings — a precursor to modern pre‑flight discipline.

The history of Cardross with a weather description for 1895 and 1896 provides crucial context for understanding Pilcher's experimental schedule and the environmental conditions that influenced his testing. These weather records demonstrate the practical challenges of conducting aviation experiments in Scottish climate conditions, where wind, rain, and temperature variations required careful planning and adaptation.

Pilcher's choice of test sites reflected careful consideration of safety requirements and operational needs. The open fields provided space for glider launches and recovery areas in case of problems. The prevailing wind conditions at each site enabled consistent testing conditions, while the slopes provided natural launch advantages that reduced the energy required for initial lift-off.

Safety procedures developed by Pilcher, including inspection routines and launch protocols, represented early examples of systematic aviation safety practices. These procedures demonstrated recognition of the inherent risks in experimental flight and the importance of systematic preparation and inspection. The documentation of these safety measures provides valuable insights into early aviation risk management.

Public Exhibitions and Demonstrations

Pilcher displayed his Hawk, which killed him, at Kelvingrove Park and Prof Square, University of Glasgow. These public exhibitions demonstrate Pilcher's commitment to sharing his work with the broader community and advancing public understanding of aviation possibilities. The displays at these prominent Glasgow locations indicate the significance attributed to Pilcher's achievements and the public interest in aviation development.

The exhibitions at Kelvingrove Park and University of Glasgow provided opportunities for public education and demonstration of aviation progress. These events connected Pilcher's experimental work with Scotland's intellectual and cultural communities, fostering broader interest in aviation development. The public exposure of the Hawk glider illustrates Pilcher's recognition of the importance of public engagement in advancing aviation understanding.

The Hawk's display at these locations would have attracted significant attention, given the novelty of controlled flight experiments in 1890s Scotland. These exhibitions served multiple purposes: demonstrating Pilcher's achievements, educating the public about aviation possibilities, and attracting potential supporters or collaborators for his experimental programme. The public interest generated by these displays reflects the broader fascination with flight that characterized the late nineteenth century.

Yachting and Maritime Connections

Pilcher sailed his yachts on the Firth of Clyde and this aspect of his life is fully explored in the book. His two yachts were Gleam and Widow. Gleam was built by the Herreshoff Brothers in America and Widow built by John Paul & Son, Gourock. Herreshoff and John Paul are covered extensively in the appendix, providing detailed information about these yacht builders and their connections to Pilcher's maritime activities.

John Herreshoff sailed on the Firth of Clyde out of Gourock and met Pilcher, creating a connection between American yacht building expertise and Scottish aviation development. This maritime connection illustrates how Pilcher's interests extended beyond aviation to encompass broader engineering and maritime pursuits. The yachting activities demonstrate Pilcher's appreciation of aerodynamics and fluid dynamics principles that are relevant to both sailing and flight.

The Firth of Clyde provided ideal sailing conditions and connected Pilcher with Scotland's maritime community. His yachting activities demonstrate his practical interest in fluid dynamics and control systems, knowledge that would have informed his aviation experiments. The connection between yachting and aviation reflects the interdisciplinary nature of early aviation development, where knowledge from various fields contributed to progress in flight.

Pilcher's ownership of Gleam and Widow demonstrates his financial resources and commitment to maritime pursuits. These yachts represented significant investments that enabled Pilcher to pursue his interests in both sailing and aviation. The detailed documentation of these yachts and their builders provides valuable insights into Pilcher's broader engineering interests and the maritime context of his aviation work.

University Lectures and Academic Contributions

Percy Sinclair Pilcher lectured at the University of Glasgow and some of his presentations are here described in the book. These lectures demonstrate Pilcher's commitment to sharing knowledge and advancing understanding of aviation principles within the academic community. His position at the university provided a platform for disseminating his experimental findings and engaging with Scotland's intellectual community.

The lectures at Glasgow University enabled Pilcher to communicate his experimental results and theoretical insights to students and colleagues. These presentations would have covered topics including glider design principles, flight control techniques, structural engineering considerations, and the practical challenges of aviation experimentation. The documentation of these lectures provides valuable insights into how Pilcher organized and communicated his knowledge.

Pilcher's academic position provided access to resources, facilities, and intellectual communities that supported his experimental work. The university environment enabled connections with other researchers, access to engineering knowledge, and opportunities for collaboration. This academic context distinguishes Pilcher's approach from purely practical experimenters and demonstrates his integration of theoretical understanding with practical experimentation.

The combination of academic knowledge and practical experimentation characterizes Pilcher's approach to aviation development. His university lectures served as a bridge between theoretical understanding and practical application, enabling him to organize and communicate his experimental findings while engaging with broader scientific and engineering communities.

The 1899 Accident and Its Aftermath

Pilcher's fatal crash in September 1899 ended a trajectory of measured progress. Contemporary accounts describe structural failure in adverse conditions during a demonstration flight, leading to unrecoverable descent. The shock reverberated through British aeronautical circles, delaying momentum toward powered tests and re‑centring focus on continental developments until the next decade.

The book provides detailed documentation of Pilcher's death, supported by the Coroner's report and conclusions. This official documentation provides authoritative information about the circumstances of the accident and the technical factors that contributed to the crash. The Coroner's report represents a crucial historical document that preserves factual details about one of aviation's earliest fatal accidents.

Pilcher's sister was instrumental in building the wings and saw him fall to his death like Icarus in September 1899. This personal tragedy illustrates the human cost of early aviation experimentation and the risks undertaken by pioneers. The involvement of family members in Pilcher's work demonstrates the personal commitment and sacrifice that characterized early aviation development.

The impact of Pilcher's death extended beyond personal tragedy to affect the broader course of British aviation development. The loss of such a promising pioneer delayed British progress toward powered flight and shifted attention to continental developments. The accident's documentation serves as a reminder of the risks inherent in experimental aviation and the importance of safety considerations in flight development.

The structural failure that led to Pilcher's death occurred during adverse conditions, demonstrating the challenges of managing flight in variable weather. This accident illustrates the importance of understanding structural limits and environmental factors in aviation safety. The lessons learned from Pilcher's accident contributed to improved safety practices in later aviation development.

Assessment and Counterfactual

Would Pilcher have achieved powered, sustained flight? The question invites caution. What can be said is this: his engineering method, results to date, and explicit power‑to‑weight planning placed him at the frontier in 1899. Incremental, well‑instrumented trials might plausibly have yielded repeatable hops and, with iterative refinement, brief sustained circuits. In that scenario, Scottish fields may have claimed a first of world historical significance.

Pilcher's systematic approach to glider development, combined with his detailed plans for powered flight, suggests that he was well-positioned to achieve powered flight success. His iterative methodology, attention to structural design, and understanding of control principles created a foundation for powered flight development. The Wright Brothers' use of Pilcher's data demonstrates the value of his research to subsequent powered flight achievements.

The documentation of Pilcher's powered flight plans provides evidence of his systematic approach to solving the propulsion challenge. His calculations and design considerations demonstrate sophisticated understanding of the technical requirements for powered flight. While we cannot know with certainty whether Pilcher would have succeeded, the evidence suggests he was on a trajectory that could have led to powered flight success.

Pilcher's achievements in glider development represent significant contributions to aviation progress even without powered flight. His systematic approach to experimentation, documentation of results, and sharing of knowledge created valuable foundations for subsequent aviation development. The influence of his work on the Wright Brothers demonstrates his important role in the cumulative progress toward powered flight.

Legacy and Scottish Aviation

Pilcher's influence persisted in two ways: first, as a methodological exemplar of engineering discipline applied to flight; second, as an inspiration for later Scottish participation in aviation — from airship works at Inchinnan to licensed aircraft and component production on Clydeside. His story links glider‑age experiment directly to Scotland's 20th‑century aviation manufacturing arc.

The Pilcher Hawk still exists today in Edinburgh, preserved as a testament to Pilcher's engineering achievements. This preservation ensures that future generations can study Pilcher's construction techniques and appreciate the sophistication of his design approach. The Hawk's survival represents a unique historical artifact that connects modern audiences with Scotland's pioneering aviation heritage.

Pilcher's methodological approach to aviation experimentation influenced subsequent Scottish aviation development. The systematic approach, attention to detail, and integration of theoretical understanding with practical experimentation characterize Scottish aviation development throughout the twentieth century. This methodological legacy extends beyond individual achievements to influence broader approaches to aviation research and development.

The connection between Pilcher's pioneering work and later Scottish aviation achievements demonstrates the continuity of aviation development in Scotland. From glider experiments in the 1890s to airship construction and aircraft manufacturing in the twentieth century, Scottish aviation development reflects methodological principles established by pioneers like Pilcher. For comprehensive coverage of this development, see Clydeside Aviation Volume One: The Great War.

Pilcher's legacy extends beyond Scotland to influence international aviation development. His contributions to glider design, his systematic approach to experimentation, and his documentation of results created valuable foundations for subsequent aviation progress. The recognition of his achievements by contemporaries like the Wright Brothers demonstrates his important role in the cumulative progress toward powered flight.

Academic Recognition and Historical Importance

The book Soaring with Wings: Percy Pilcher wants to Fly has been described as "a remarkable piece of scholarship and does Percy justice" in recent reviews. The 171-page biography, profusely illustrated with many rare and interesting pictures and drawings, provides comprehensive documentation of Pilcher's four years of experimental flying. Printed on high quality paper making it very heavy, the book represents a highly recommended limited run publication that preserves Pilcher's story for future generations.

The book's dedication to the late Dieter Dengler, US Navy escaped pilot in the Vietnam war, who was the first escape from Laos in 1966, creates a connection between early aviation pioneers and later aviation heroes. This dedication reflects the continuity of courage and determination that characterizes aviation development across different eras and contexts.

The comprehensive bibliography and appendix included in the book provide valuable resources for researchers studying Pilcher's work and its historical context. These scholarly features ensure that the book meets academic standards while remaining accessible to general readers interested in aviation history and Scottish heritage.

The detailed documentation of Pilcher's experimental work, contacts, and achievements creates a comprehensive resource for understanding early aviation development in Scotland. The book's thorough research and careful documentation preserve crucial historical information that might otherwise be lost, ensuring that Pilcher's contributions to aviation progress are properly recognized and studied.

Conclusion: A Scottish Pioneer's Enduring Legacy

Percy Pilcher's disciplined experiment, Scottish setting, and near‑term powered flight plan warrant his remembrance as a principal founder of practical aviation. His programme exemplified the engineering virtues that sustain aeronautics to this day: iterate carefully, measure honestly, and fly what you can prove. His untimely death in 1899 represents one of aviation's greatest losses, cutting short a trajectory that might have achieved powered flight before the Wright Brothers.

Pilcher's achievements in glider development, his systematic approach to experimentation, and his influence on subsequent aviation pioneers demonstrate his important role in aviation history. The preservation of the Hawk glider in Edinburgh, the documentation of his work in comprehensive biographies, and the recognition of his contributions by contemporaries ensure that his legacy continues to inspire and inform aviation development.

The comprehensive documentation provided in Charles E. MacKay's biography ensures that Pilcher's remarkable story is preserved for future generations. The book's thorough research, detailed illustrations, and careful documentation create an authoritative resource that does justice to Pilcher's achievements and contributions to aviation progress. This scholarly work ensures that Scotland's forgotten aviation pioneer receives the recognition his achievements deserve.

Further Reading and Related Works

For comprehensive coverage of Percy Pilcher's life and achievements, explore these authoritative works by Charles E. MacKay:

- Soaring with Wings: Percy Pilcher wants to Fly — The definitive 171-page biography profusely illustrated with many rare and interesting pictures and drawings, documenting Pilcher's four years of experimental flying

- Clydeside Aviation Volume One: The Great War — Comprehensive coverage of aviation on Clydeside from 1785 to 1919, including Pilcher's pioneering work and the broader Scottish aviation context

- British Aircraft of the Great War — Reference foundation for pre‑war to wartime transition, documenting how Pilcher's pioneering work influenced later aviation development

- Dieter Dengler, Skyraider 04 Down — Dedicated to the late Dieter Dengler, US Navy escaped pilot, creating a connection between aviation pioneers and later aviation heroes

Related Articles

- The Clydeside Aviation Revolution — Regional ecosystem and capability build‑up that built upon Pilcher's pioneering work

- Beardmore Aviation: Scottish Industrial Giant — How Scottish industrial expertise transformed into aviation manufacturing, continuing Pilcher's legacy

References

- Royal Air Force Museum — Aircraft Collection — Royal Air Force Museum

- Imperial War Museums — Aviation History Articles — Imperial War Museums

- FlightGlobal Archive — FlightGlobal