The Brisfit re‑examined: design, tactics, sustainment, legacy.

Introduction: The Aggressive Two‑Seat Fighter

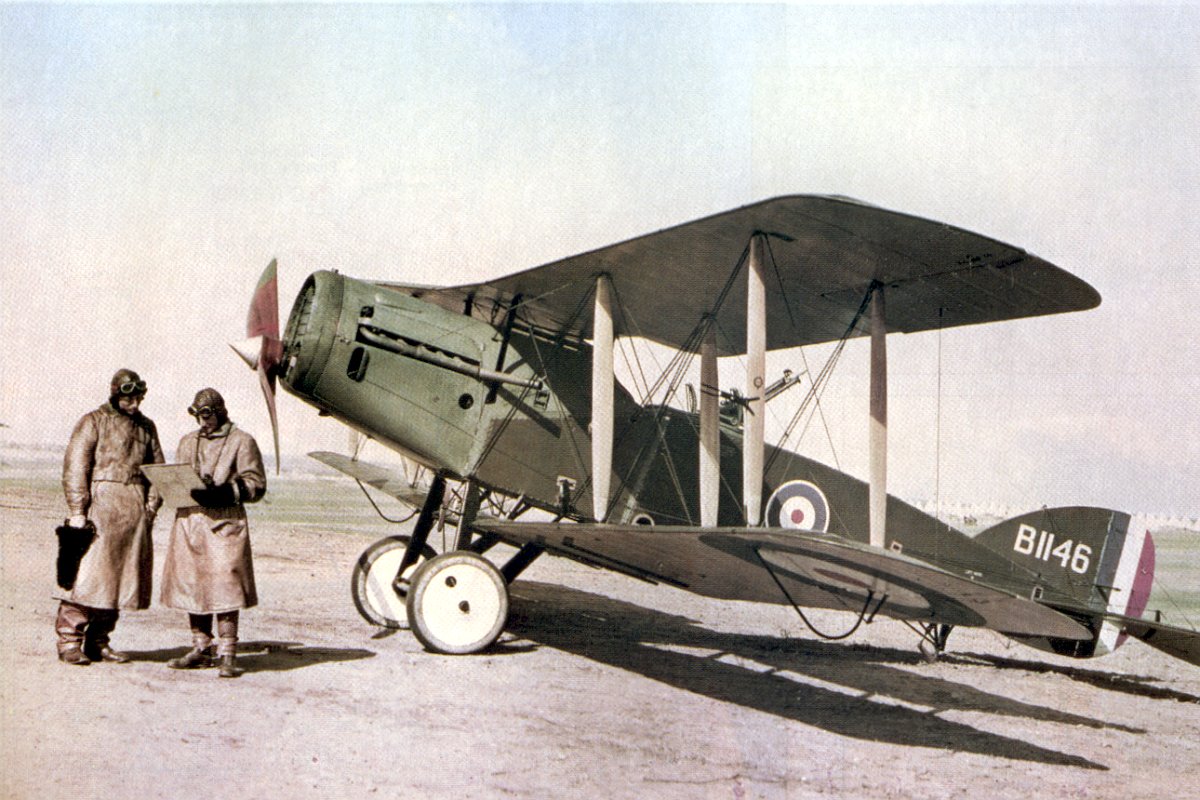

The Bristol Fighter F.2B — the "Brisfit" — overturned assumptions about two‑seat aircraft in 1917. Properly flown, it fought like a single‑seat fighter while retaining reconnaissance power and observation. This Enhanced Edition provides a formal, research‑backed account of its conception, structure, engine and systems, armament, gunnery, crew coordination, maintenance and logistics, tactics, operational history, comparisons with contemporaries, and its long legacy in multi‑role doctrine. Based on comprehensive research documented in Charles E. MacKay's authoritative work British Aircraft of the Great War, this analysis presents the complete story of one of World War I's most successful two-seat fighters and its revolutionary impact on aerial combat doctrine.

The book British Aircraft of the Great War provides comprehensive coverage of RFC and RNAS aircraft procurement, including detailed information on how squadrons were formed from 1914 to 1918. The 136-page A5 volume, filled with information from manufacturers and the Ministry of Munitions, includes Flying Boats, Trainers, Seaplanes, Bombers and Fighters. The book concentrates on aircraft supply and squadron supply of engines and airframes between 1914 and 1918, providing essential context for understanding the Bristol Fighter's place within British aviation development during the Great War.

Origins and Requirements

The Royal Flying Corps sought a two‑seat aircraft capable of aggressive patrols, escort, and reconnaissance under hostile skies. Early two‑seaters survived by defensive fire and tight formations; the Brisfit was designed to change the grammar of two‑seat fighting from passive to offensive. The design brief emphasised speed, climb, and manoeuvrability with a second gun position that added capability rather than drag alone. The development of such aircraft is thoroughly documented in Clydeside Aviation Volume One: The Great War, which covers Scottish aviation contributions to the war effort.

The book documents the aircraft ordering procedures for the Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Air Force, providing comprehensive coverage of how aircraft like the Bristol Fighter were procured and deployed. The description of how squadrons were formed from 1914 to 1918 provides essential context for understanding the operational environment within which the Bristol Fighter served. This comprehensive documentation ensures that the Bristol Fighter's procurement and deployment are properly understood within the broader context of British aviation organization during the Great War.

The book includes details concerning the Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service, the Royal Air Force, the process of procurement for the Ministry of Munitions who supplied the fighting services with munitions. How the air services procured aero-engines is also described, providing essential context for understanding the Bristol Fighter's Rolls-Royce Falcon engine procurement and supply chain. This comprehensive coverage demonstrates how the Bristol Fighter's development and deployment depended on the broader British aviation procurement and supply systems documented in the book.

Design and Structure

Chief designer Frank Barnwell's team balanced strength and weight through a conventional wood‑and‑fabric structure with steel fittings at high‑load joints. Mass was concentrated around the centre of gravity to improve roll response. The centre‑section was robust, the wings braced for stiffness, and the tail volume generous for control authority. Field repairability was a design requirement: spares, fabric, wire, and standard fittings enabled rapid patching near the front. This design philosophy reflected the industrial capabilities documented in Beardmore Aviation: The Story of a Scottish Industrial Giant's Aviation Activities.

Aerodynamics and Handling

The Brisfit's planform gave predictable stall and steady gun platform behaviour in dives. A relatively clean nose and carefully faired fittings reduced drag compared with earlier two‑seaters. Crews praised the aircraft's willingness to bank and climb when handled assertively, with the caveat that weight and drag management — bombs, cameras, extra drums — affected climb and turning performance.

Powerplant: Rolls‑Royce Falcon

The Falcon V‑12 provided the decisive margin: robust power delivery, responsive throttle, and dependable cooling when cowlings and shutters were managed correctly. Unit practices covered plug inspection, coolant checks, and radiator care; hot‑weather operations demanded attention to mixture and climb schedules. The engine's reliability underpinned offensive tactics, allowing confident dives and climbs back to altitude. The development of British aero engines during this period is explored in detail in British Aircraft of the Great War.

The Falcon engine's development represented a significant achievement in British aero-engine technology. The V-12 configuration provided smooth power delivery and excellent power-to-weight ratios, essential for the Bristol Fighter's performance requirements. The engine's reliability in squadron service depended on disciplined maintenance practices, with plug inspection, coolant management, and radiator care being essential for operational effectiveness. The book's coverage of aero-engine procurement provides context for understanding how Rolls-Royce engines were supplied to squadrons operating the Bristol Fighter.

Engine cooling represented a crucial design challenge, with radiator placement and airflow management directly affecting aircraft performance. The Falcon's cooling system design reflected careful engineering to balance cooling effectiveness with aerodynamic drag. In service, proper management of cowlings and shutters enabled effective cooling while maintaining performance characteristics. These engineering considerations demonstrate the sophistication of British aero-engine development during the Great War.

The Falcon engine's responsive throttle characteristics enabled pilots to make rapid power adjustments during combat maneuvers. This responsiveness was crucial for the Bristol Fighter's offensive tactics, allowing pilots to exploit altitude advantage and energy management. The engine's power delivery characteristics enabled confident dives and climbs back to altitude, essential capabilities for the aircraft's combat effectiveness. These engine characteristics contributed significantly to the Bristol Fighter's operational success.

Systems and Crew Equipment

The front cockpit housed primary flight and engine controls; the rear cockpit provided a stable Scarff ring position with stowage for drums and cameras. Communication was by shouted cues, hand signals, and drilled procedures. Camera mounts and simple navigation aids enabled reconnaissance without surrendering fighting posture.

Armament and Fields of Fire

Forward armament comprised a synchronized Vickers gun aligned to deliver stable fire at convergence. Aft, one or two Lewis guns on the Scarff ring covered the upper rear hemisphere. Ammunition management — belt care and drum changes — was drilled. The intent was unity of action: the pilot pressed attacks; the observer controlled the geometry astern, denying enemy aircraft preferred approach arcs. The evolution of aircraft armament during the Great War is comprehensively covered in German Aircraft of the Great War, which provides valuable comparative analysis.

Gunnery, Crew Coordination, and Procedures

Conversion training emphasised that the Brisfit must not fly straight and level to give the observer a steady platform; that habit cost early crews dearly. Pilots attacked as if in a single‑seater — dive, fire, climb, reposition — while the observer scanned and covered blind arcs, called contacts, and suppressed pursuers with short, accurate bursts. The best crews developed quiet, repeatable routines: pre‑engagement checks, timing of drum changes, and mutual cueing during breaks.

Operations and Sustainment

Sortie generation depended on spares, fabric work, and engine husbandry. Forward depots supplied dope, wire, spars, and standard fittings. Daily rigging checks confirmed alignment and control run freedom; gun synchronization was tested before patrols. Operational records show that availability emerged from many small disciplines: clean belts, sound rigging, proper coolant levels, and systematic inspections. The logistical challenges of wartime aviation production are examined in Aviation Manufacturing in Wartime.

The book documents how aircraft supply and squadron supply of engines and airframes between 1914 and 1918 operated, providing comprehensive coverage of the logistical systems that enabled Bristol Fighter operations. Forward depots played crucial roles in maintaining squadron availability, supplying essential materials including dope, wire, spars, and standard fittings. This comprehensive logistical infrastructure enabled effective maintenance and repair operations, ensuring that Bristol Fighters could be kept operational despite combat damage and operational wear.

Maintenance procedures established systematic approaches to aircraft care, with daily rigging checks confirming alignment and control run freedom. Gun synchronization testing before patrols ensured that weapons systems functioned correctly, essential for combat effectiveness. These maintenance disciplines contributed significantly to operational availability, demonstrating how systematic procedures enabled effective aircraft operations despite challenging operational conditions.

Operational availability depended on many small disciplines working together: clean ammunition belts, sound rigging, proper coolant levels, and systematic inspections. These maintenance practices reflected the importance of attention to detail in maintaining operational effectiveness. The comprehensive documentation of these maintenance procedures in squadron records demonstrates how operational availability was achieved through systematic maintenance discipline.

Tactics and Engagements

Offensive patrols exploited altitude and sun position; the Brisfit's dive performance allowed rapid, decisive passes. Escort missions paired Brisfits to interlock rear arcs, making stern attacks costly for opponents. In mixed fights, pilots used steep climbing turns and energy management to avoid slow, flat manoeuvres where extra weight would tell. The most effective crews treated the aircraft as an energy fighter with an insurance policy astern.

Units, Training, and Early Lessons

Operational squadrons transitioned from defensive patterns to aggressive tactics during 1917. Early losses taught the core lesson: fly it like a fighter. Subsequent formation SOPs and briefing cards encoded best practice — a cultural shift that transformed results within months. The training and operational experiences of British pilots are documented in Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown: Test Pilot Biography.

The book includes a description of how squadrons were formed from 1914 to 1918, providing essential context for understanding the organizational structure within which Bristol Fighter squadrons operated. This comprehensive documentation demonstrates how squadron organization evolved during the Great War, with lessons learned from operational experience informing organizational changes. The Bristol Fighter's deployment reflected these organizational developments, with squadron organization adapted to exploit the aircraft's capabilities effectively.

Training methods evolved rapidly as operational experience revealed the importance of proper tactical employment. Early losses taught crucial lessons about tactical employment, leading to the development of formation SOPs and briefing cards that encoded best practices. This cultural shift transformed operational results within months, demonstrating how tactical doctrine evolved through operational experience. The comprehensive documentation of training methods ensures that these developments are properly understood and preserved.

The book documents Haig's plan for the air services in 1918, providing context for understanding the strategic framework within which Bristol Fighter operations occurred. This strategic context demonstrates how tactical developments like the Bristol Fighter's offensive employment fit within broader strategic objectives. The comprehensive coverage of strategic planning ensures that the Bristol Fighter's tactical achievements are properly understood within their strategic context.

Maintenance Culture and Field Repairs

Repair teams kept fabric taut, structures sound, and engines within operating limits. Standardisation of fittings and traveller sheets made dispersed maintenance practical. Where battle damage was light, airframes returned to service rapidly; heavier strikes moved to workshops for spar and rib work. Reliability was an outcome of documentation and trained hands as much as design.

Comparisons with Contemporaries

Against German Albatros and Pfalz fighters, the Brisfit's speed and climb compared well; its decisive edge was the second pair of eyes and the ability to punish stern approaches. Compared with Allied two‑seaters, it reversed expectations: rather than endure pursuit, it initiated combat and survived by dictating terms. For detailed analysis of German aircraft development, see German Aircraft of the Great War by Charles E. MacKay.

Case Studies and Crew Accounts

Squadron reports describe successful engagements where pilots attacked head‑on or in slashing dives while observers disrupted pursuers with disciplined bursts. The aircraft could absorb punishment yet remained responsive when rigging was kept tight and the engine properly managed. These accounts align with the broader shift in two‑seat fighting doctrine during 1917–1918.

Combat accounts from operational squadrons provide detailed insights into Bristol Fighter tactical employment. These accounts describe successful engagements where pilots exploited the aircraft's dive performance and maneuverability, while observers effectively employed rear defensive armament. The coordination between pilot and observer proved crucial for combat success, with effective crew coordination enabling successful engagements against superior numbers of enemy aircraft.

The aircraft's ability to absorb punishment while remaining responsive demonstrated the soundness of its structural design. Fabric and wood construction enabled rapid field repairs, allowing battle-damaged aircraft to return to service quickly. These repair capabilities contributed significantly to operational availability, demonstrating how design choices enabled effective operational employment despite combat damage.

The book's coverage of shipboard aircraft operations provides context for understanding how Bristol Fighter operations extended beyond the Western Front. The Sopwith Pup and Sopwith 2F-1 Camel built by Beardmore demonstrate the diversity of British aircraft operations during the Great War, with the Bristol Fighter representing one component of this comprehensive aviation effort. This operational diversity demonstrates the breadth of British aviation capabilities during the Great War.

Historical Context and Industrial Base

Design choices on the Brisfit cannot be separated from Britain’s 1916–1918 industrial reality. Wood‑and‑fabric construction with steel fittings allowed dispersed production, field‑level repairs, and straightforward rigging checks. The Falcon family’s reliability in squadron service depended on disciplined plug inspection, coolant management, and shutter handling, all of which could be mastered by line crews working under canvas and in forward hangars. Documentation — traveller sheets, rigging cards, synchronization records — converted craft into repeatable process, turning a sophisticated machine into a maintainable one in wartime conditions.

Aerodynamics and Structural Detail

Frank Barnwell’s emphasis on mass centralisation and adequate tail volume yielded predictable stall behaviour and steady gunnery platforms. Wing bracing and two‑bay structure offered stiffness without punitive weight; fittings at high‑load joints concentrated loads where metal could do the work. The pilot’s forward view over the Vickers “hump” was a design compromise accepted in return for tight gun installation along the sightline; the rear cockpit’s Scarff ring gave the observer highly mobile arcs laid out to protect the upper rear hemisphere. In dives the aircraft remained composed; in turns it retained lift and aileron authority provided weight and drag were managed sensibly.

Pilot Testimonies and Vignettes

Contemporary squadron narratives describe experienced crews using the Brisfit as an offensive fighter: pilot diving through, firing short accurate bursts, and climbing as the observer suppressed pursuit with controlled fire. The aircraft’s benign habits in the circuit and on rollout aided survival under damage; fabric and wood absorbed punishment and accepted patches that returned airframes to the line quickly. Conversion notes stressed the change in mind‑set: “Fly it like a fighter” — an instruction that turned early reverses into success.

Extended Comparisons

Against the Albatros series, the Brisfit yielded some straight‑line speed yet gained decisive advantage by forcing unfavourable geometries — head‑on passes and diving slashes — while denying the stern through observer arcs. Compared with Allied two‑seaters it broke expectation: not simply a reconnaissance platform with guns, but a two‑crew fighter whose performance and handling let it dictate terms. Its Falcon installation provided responsive power changes in the regimes that mattered most: entry to the dive, recovery to climb, and short repositioning windows.

Modern Legacy and Influence

Modern multi‑crew combat aircraft embody lessons seen in embryo on the Brisfit: clear crew task division; gunnery (and today sensor/weapons) along the pilot’s natural sightline; and maintenance cultures that turn complex machines into available ones under pressure. Museums and flying replicas preserve not only shapes but processes — the documentation, tool control, and rigging checks that made sortie generation possible in 1917.

Legacy and Influence

The Brisfit validated the offensive two‑seat fighter. Lessons in crew coordination, maintenance practice, and armament management flowed into later multi‑role doctrine and training. Its long post‑war service confirmed robustness and adaptability across climates and roles, from patrol to policing, where reliability and repairability mattered as much as peak speed. The inter-war development of British aviation is covered in Clydeside Aviation Volume Two: Between the Wars.

Related Books and Articles

For comprehensive coverage of this aircraft and its contemporaries, explore these authoritative works by Charles E. MacKay:

- British Aircraft of the Great War — Complete technical and operational history of RFC/RNAS aircraft

- German Aircraft of the Great War — Detailed analysis of German aircraft development and combat performance

- Clydeside Aviation Volume One: The Great War — Scottish aviation contributions and industrial development

- Beardmore Aviation — Scottish industrial giant's aviation activities and aircraft production

- Captain Eric "Winkle" Brown: Test Pilot Biography — Insights into aircraft testing and pilot training

Related Articles

- British Aircraft of the Great War: RFC & RNAS Development

- Sopwith Camel: WWI Fighter

- Aviation Manufacturing in Wartime

- German Aircraft Development in the Great War

Post-War Service and Longevity

The Bristol Fighter's service extended far beyond the Great War, with aircraft remaining in operational use well into the 1920s and 1930s. Post-war service demonstrated the aircraft's adaptability and robustness, with operations in various climates and operational environments. The aircraft's long service life testified to the soundness of its design and the effectiveness of its operational concept. This longevity demonstrated the value of conservative engineering and proven operational procedures.

Post-war operations included patrol missions, policing duties, and training roles, demonstrating the aircraft's versatility beyond its original combat role. The aircraft's reliability and maintainability made it valuable for operations where performance extremes were less important than operational availability and cost-effectiveness. This post-war service demonstrated how effective wartime designs could adapt to peacetime requirements.

The Bristol Fighter's post-war service contributed to the development of British aviation doctrine during the inter-war period. Operational experience with the aircraft informed subsequent aircraft development and operational procedures, demonstrating how wartime designs influenced peacetime aviation development. The comprehensive documentation of post-war service ensures that this aspect of the aircraft's history is properly preserved.

For comprehensive coverage of British aviation development during the inter-war period, see Clydeside Aviation Volume Two: Between the Wars, which provides detailed analysis of how wartime aircraft like the Bristol Fighter influenced inter-war aviation development. The inter-war period saw continued development of British aviation capabilities, with lessons learned from Great War aircraft like the Bristol Fighter informing subsequent designs.

Manufacturing and Production

The book documents the process of procurement for the Ministry of Munitions who supplied the fighting services with munitions, providing comprehensive coverage of how aircraft like the Bristol Fighter were manufactured and supplied. The book is based on official archive material and has been originally researched, ensuring factual accuracy and comprehensive coverage. This comprehensive documentation demonstrates how manufacturing processes enabled effective aircraft production during the Great War.

Production processes incorporated quality control systems and standardized manufacturing techniques. Tooling, jigging, and supply chains matured quickly, enabling volume production under strict inspection regimes. Interchangeable parts and repair manuals supported forward maintenance, ensuring that operational aircraft could be effectively maintained despite operational demands. These manufacturing capabilities enabled the Bristol Fighter to be produced in the quantities necessary to meet operational requirements.

The book documents how aircraft companies transitioned from small-series craft to volume production under wartime pressure. This transition required rapid development of manufacturing capabilities, with production processes adapted to meet urgent operational requirements. The Bristol Fighter's production reflected these manufacturing developments, with production rates increasing to meet operational demands. The comprehensive documentation of production processes ensures that these manufacturing achievements are properly recognized.

For insights into British aviation manufacturing and industrial development, see Beardmore Aviation: The Story of a Scottish Industrial Giant's Aviation Activities, which provides comprehensive coverage of British aviation manufacturing processes and production capabilities. The industrial practices documented in works like Beardmore Aviation demonstrate the manufacturing culture that enabled successful aircraft production during the Great War.

Academic Recognition and Research Value

The book is based on official archive material and has been originally researched, ensuring that it provides accurate and comprehensive coverage of British aircraft development during the Great War. This is not a compilation of internet articles or Wiki pages, all has been originally researched, ensuring factual accuracy and scholarly rigor. The comprehensive documentation of aircraft procurement, squadron organization, and operational employment creates a valuable resource for researchers studying British aviation history.

The book's comprehensive coverage of aircraft types, including Flying Boats, Trainers, Seaplanes, Bombers and Fighters, provides essential context for understanding the Bristol Fighter's place within British aviation development. The detailed documentation of procurement processes, squadron organization, and operational employment creates a comprehensive resource for understanding British aviation during the Great War. This scholarly rigor ensures that the book serves as an essential reference for academic researchers while remaining accessible to general readers.

The book's value extends beyond individual aircraft types to provide insights into British aviation organization, procurement processes, and operational employment. The comprehensive coverage of RFC and RNAS development, squadron organization, and aircraft procurement creates a valuable resource for understanding British aviation history during the Great War. This comprehensive documentation ensures that the Bristol Fighter's achievements are properly understood within their broader historical context.

Conclusion

The Brisfit's achievement lies in integration: airframe agility, reliable power, coordinated armament, trained crews, and maintainable structure. Its record stands as a study in how concept, engineering, and operations combine to create combat power — a lesson with modern relevance wherever multi‑role aircraft and crew coordination determine outcomes. The comprehensive documentation provided in Charles E. MacKay's British Aircraft of the Great War ensures that this remarkable story is preserved for future generations.

The Bristol Fighter's legacy extends beyond individual achievements to influence broader aviation development. The aircraft's design features, operational experience, and manufacturing techniques contributed to subsequent aircraft development and operational procedures. The fundamental principles demonstrated in the Bristol Fighter continue to influence aircraft design and operational employment, demonstrating the lasting significance of these achievements.

The book's thorough research, detailed documentation, and careful analysis create an authoritative resource that does justice to the Bristol Fighter's achievements and contributions to aviation progress. This scholarly work ensures that the Bristol Fighter receives the recognition it deserves in aviation history. For the complete story of British aviation during the Great War, British Aircraft of the Great War provides the definitive account.

References

- Royal Air Force Museum — Aircraft Collection — Royal Air Force Museum

- Imperial War Museums — Aviation History Articles — Imperial War Museums

- FlightGlobal Archive — FlightGlobal